Any time I write about vaccines, especially mRNA vaccines, things get dicey. Any negative comments might fuel attacks from one wing that I’m trying to fuel vaccine doubt, or (from another), hostility toward corporate innovation and profits. And of course, there’s a small but vocal minority that believes that all vaccines are inherently harmful; it’s hard (some say impossible) to reason with this group.

Still, this recent episode involving Moderna’s mRNA influenza vaccine is too important for card-carrying ID doctors like me to ignore. So here we go.

What Happened — the Meaning of “Acceptable” (and the FDA Leadership) Changed

Moderna conducted a large, global, randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial of its mRNA seasonal influenza vaccine, enrolling roughly 40,000 participants. Such studies are enormous undertakings; they represent hundreds of millions of dollars in investment and thousands of participants’ and investigators’ time and trust.

The control arm used a licensed, standard-dose influenza vaccine. According to company statements, the FDA had previously cleared this trial design.

Did they? Moderna quotes the FDA’s guidance they received before the study started:

While we agree it would be acceptable to use a licensed standard dose influenza vaccine as the comparator in your Phase 3 study, we recommend you use a vaccine preferentially recommended for use in older adults by the ACIP (i.e., Fluzone HD, Fluad or Flublok) for participants >65 years of age in the study. Data on comparative efficacy of your vaccine against an influenza vaccine preferentially recommended for use in the >65 years age group may help inform ACIP’s recommendation for the use of your vaccine in the older adult population. If you proceed with using a standard dose influenza vaccine comparator in participants ≥65 years of age, we agree with your plan to include statements in the Informed Consent Form.

That word — acceptable — is right there in the first sentence, subsequent caveats notwithstanding. The study went forward with the standard-dose vaccine.

After the trial was completed and submitted, however, on February 3 the FDA declined to review the application; here’s why:

This is because your control arm does not reflect the best-available standard of care in the United States at the time of the study. I note that this determination is consistent with FDA’s advice given to you prior to your study.

Jeepers. I guess “acceptable” wasn’t “acceptable” after all!

Regulators do sometimes reconsider positions as new data emerge — especially when a transformative study changes the standard of care.

But here, regarding the efficacy of the high-dose vaccine in older adults, the data are mixed — one study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a benefit, another study (in the same issue) didn’t. And even though the high-dose vaccine is recommended for older adults here in the United States, this is not routine practice globally, including in some of the countries Moderna ran the study.

Should the FDA have formally reviewed the study given this sequence of events? I believe so. And if the agency had serious concerns about the adequacy of the control arm for older participants, those concerns should have been made unmistakably clear before the trial was launched.

The very fact that the head of Health and Human Services has a well-known reputation for anti-vaccine views raises concerns that this “refuse to file” action had political motivations, though no doubt the FDA would deny this. Importantly, there would be no requirement, after review, that the FDA fully approve the vaccine for use in the U.S. market. They could review it, provide formal feedback about what additional data are needed, and await a response from Moderna.

Another Disappointment — The Data

The regulatory controversy generated headlines, but disappointing in a different way are the results — not just of the Moderna mRNA flu study (October 23, 2025 presentation), but also one conducted by Pfizer for its own vaccine.

Moderna’s large trial indicated a modest but statistically significant reduction in symptomatic influenza illness relative to standard vaccination — about 27% better (2.1% vs 2.7%) — with efficacy consistent across baseline age groups. Pfizer’s phase 3 study also showed superiority over licensed influenza vaccines, with a relative vaccine efficacy of 35% against symptomatic illness; however, in subgroup analyses of older adults, the prespecified noninferiority criterion was not met. Neither program demonstrated clear differences in hospitalization or death, which are difficult to power for in seasonal influenza trials, as these events are rare.

The real problem, however, is the tolerability profile of these vaccines. They trigger more short-term symptoms than the number of influenza cases they prevent. Given the low absolute risk of influenza in these trials (<3%), symptoms of fever (6%) and chills (23%) were more common after mRNA vaccination than laboratory-confirmed influenza in either arm of the study. The company slide set characterizes these reactions as “mostly mild to moderate and of short duration” — yes, this is true, but at the same time they occurred more frequently than with the standard flu vaccine.

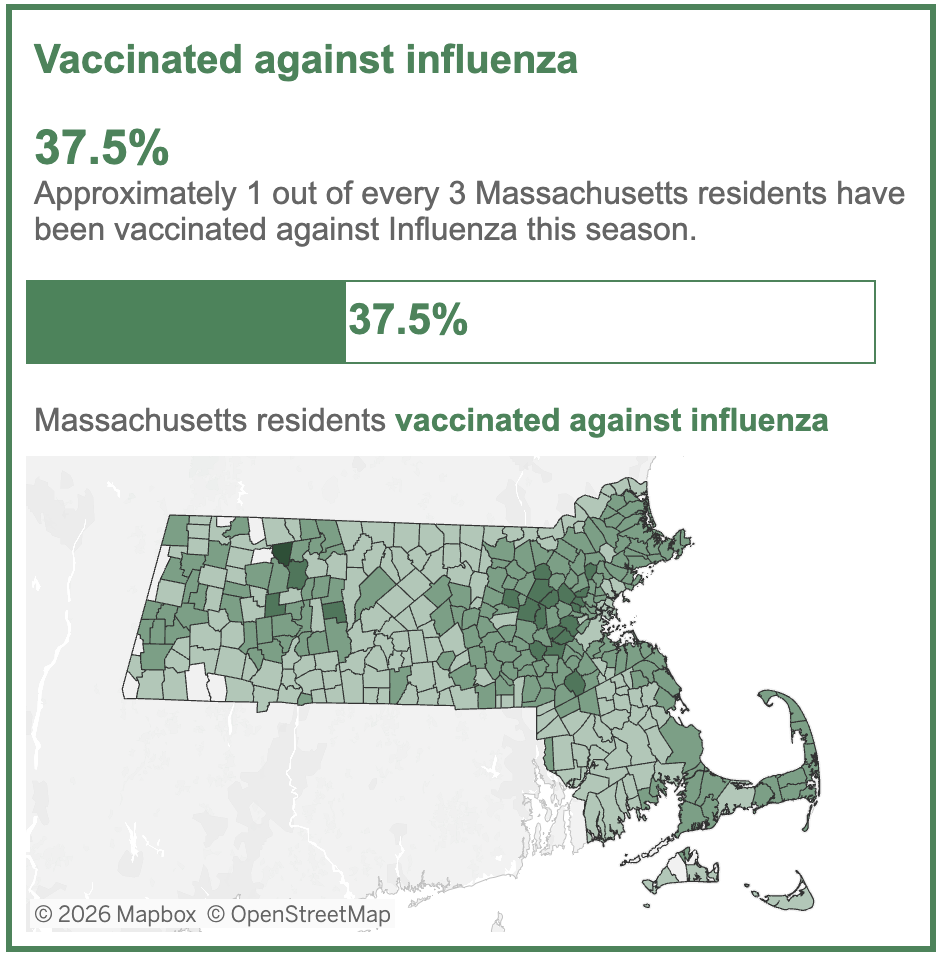

If the adverse events are transient, why does this matter? Seasonal influenza vaccination is not a one-time emergency intervention; it is an annual recommendation given to healthy children and adults alike. Despite this broad recommendation, enthusiasm for this vaccine among the public is already lukewarm at best. Here are this year’s data from Massachusetts:

Vaccines that cause more short-term side effects without clearly superior clinical benefit will be a very hard sell in the clinic, especially on a yearly basis.

A Broader Perspective

This decision and these results are particularly disappointing given what mRNA technology demonstrated in 2020 in response to Covid-19. Traditional influenza vaccine production remains slow, dependent on strain selection months in advance and, in many cases, egg-based manufacturing. In the face of a novel pandemic strain — H5N1, H7N9, or something entirely new — the ability to design and scale a matched vaccine within weeks rather than months could be transformative.

Sometimes I’m asked what keeps me up at night in the ID universe; right up there, it’s that one of these novel flu strains becomes highly transmissible, and we’re stuck with the old way of making a flu vaccine. A formal review by the FDA of the Moderna data might have clarified a regulatory pathway for rapid approval of a strain-matched vaccine in the event of a pandemic.

One hopes that a formal review of the data ultimately occurs, with pandemic preparedness in mind.

To your last point, I came across the following sadness this morning: “Staff members at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) have been told to delete the words “biodefense” and “pandemic preparedness” from the institute’s website, a move that experts say will hobble the United States’ ability to respond to future infectious disease threats, Nature reported late last week.”

Reply