An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 17th, 2026

Two Things Can Be True: The FDA Process Was Inconsistent, and the mRNA Vaccine Data Were Disappointing

Any time I write about vaccines, especially mRNA vaccines, things get dicey. Any negative comments might fuel attacks from one wing that I’m trying to fuel vaccine doubt, or (from another), hostility toward corporate innovation and profits. And of course, there’s a small but vocal minority that believes that all vaccines are inherently harmful; it’s hard (some say impossible) to reason with this group.

Still, this recent episode involving Moderna’s mRNA influenza vaccine is too important for card-carrying ID doctors like me to ignore. So here we go.

What Happened — the Meaning of “Acceptable” (and the FDA Leadership) Changed

Moderna conducted a large, global, randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial of its mRNA seasonal influenza vaccine, enrolling roughly 40,000 participants. Such studies are enormous undertakings; they represent hundreds of millions of dollars in investment and thousands of participants’ and investigators’ time and trust.

The control arm used a licensed, standard-dose influenza vaccine. According to company statements, the FDA had previously cleared this trial design.

Did they? Moderna quotes the FDA’s guidance they received before the study started:

While we agree it would be acceptable to use a licensed standard dose influenza vaccine as the comparator in your Phase 3 study, we recommend you use a vaccine preferentially recommended for use in older adults by the ACIP (i.e., Fluzone HD, Fluad or Flublok) for participants >65 years of age in the study. Data on comparative efficacy of your vaccine against an influenza vaccine preferentially recommended for use in the >65 years age group may help inform ACIP’s recommendation for the use of your vaccine in the older adult population. If you proceed with using a standard dose influenza vaccine comparator in participants ≥65 years of age, we agree with your plan to include statements in the Informed Consent Form.

That word — acceptable — is right there in the first sentence, subsequent caveats notwithstanding. The study went forward with the standard-dose vaccine.

After the trial was completed and submitted, however, on February 3 the FDA declined to review the application; here’s why:

This is because your control arm does not reflect the best-available standard of care in the United States at the time of the study. I note that this determination is consistent with FDA’s advice given to you prior to your study.

Jeepers. I guess “acceptable” wasn’t “acceptable” after all!

Regulators do sometimes reconsider positions as new data emerge — especially when a transformative study changes the standard of care.

But here, regarding the efficacy of the high-dose vaccine in older adults, the data are mixed — one study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a benefit, another study (in the same issue) didn’t. And even though the high-dose vaccine is recommended for older adults here in the United States, this is not routine practice globally, including in some of the countries Moderna ran the study.

Should the FDA have formally reviewed the study given this sequence of events? I believe so. And if the agency had serious concerns about the adequacy of the control arm for older participants, those concerns should have been made unmistakably clear before the trial was launched.

The very fact that the head of Health and Human Services has a well-known reputation for anti-vaccine views raises concerns that this “refuse to file” action had political motivations, though no doubt the FDA would deny this. Importantly, there would be no requirement, after review, that the FDA fully approve the vaccine for use in the U.S. market. They could review it, provide formal feedback about what additional data are needed, and await a response from Moderna.

Another Disappointment — The Data

The regulatory controversy generated headlines, but disappointing in a different way are the results — not just of the Moderna mRNA flu study (October 23, 2025 presentation), but also one conducted by Pfizer for its own vaccine.

Moderna’s large trial indicated a modest but statistically significant reduction in symptomatic influenza illness relative to standard vaccination — about 27% better (2.1% vs 2.7%) — with efficacy consistent across baseline age groups. Pfizer’s phase 3 study also showed superiority over licensed influenza vaccines, with a relative vaccine efficacy of 35% against symptomatic illness; however, in subgroup analyses of older adults, the prespecified noninferiority criterion was not met. Neither program demonstrated clear differences in hospitalization or death, which are difficult to power for in seasonal influenza trials, as these events are rare.

The real problem, however, is the tolerability profile of these vaccines. They trigger more short-term symptoms than the number of influenza cases they prevent. Given the low absolute risk of influenza in these trials (<3%), symptoms of fever (6%) and chills (23%) were more common after mRNA vaccination than laboratory-confirmed influenza in either arm of the study. The company slide set characterizes these reactions as “mostly mild to moderate and of short duration” — yes, this is true, but at the same time they occurred more frequently than with the standard flu vaccine.

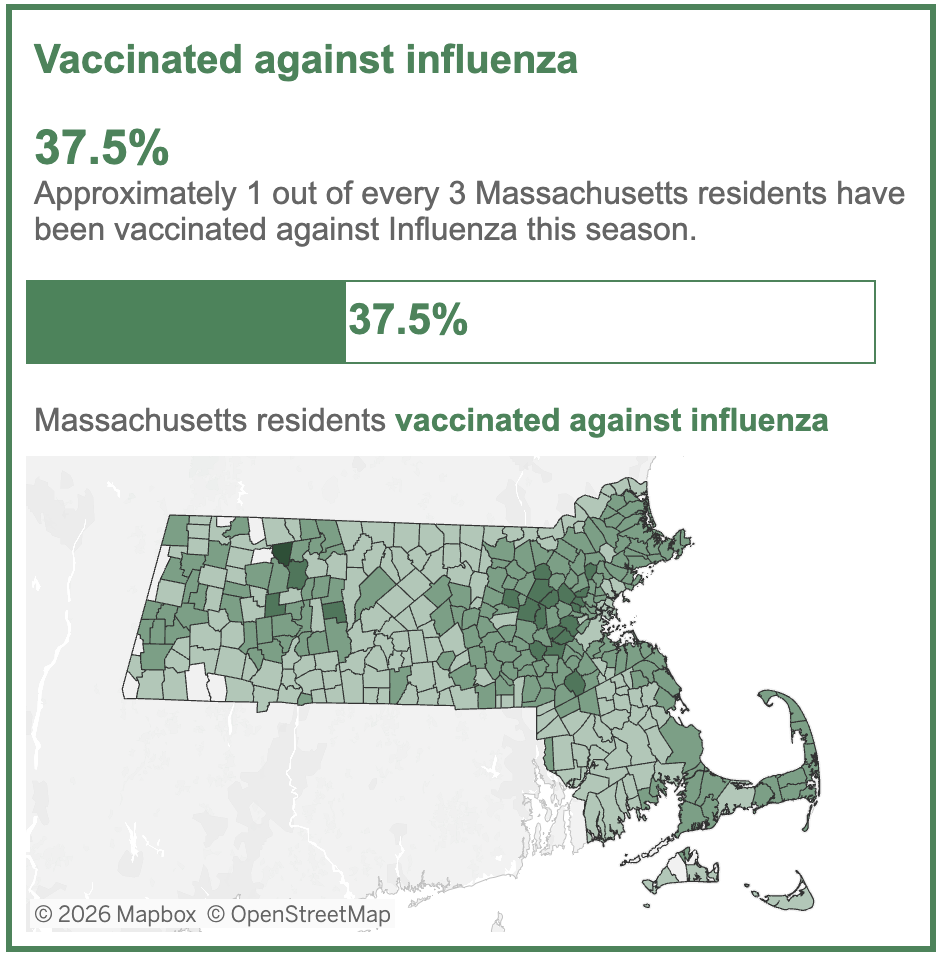

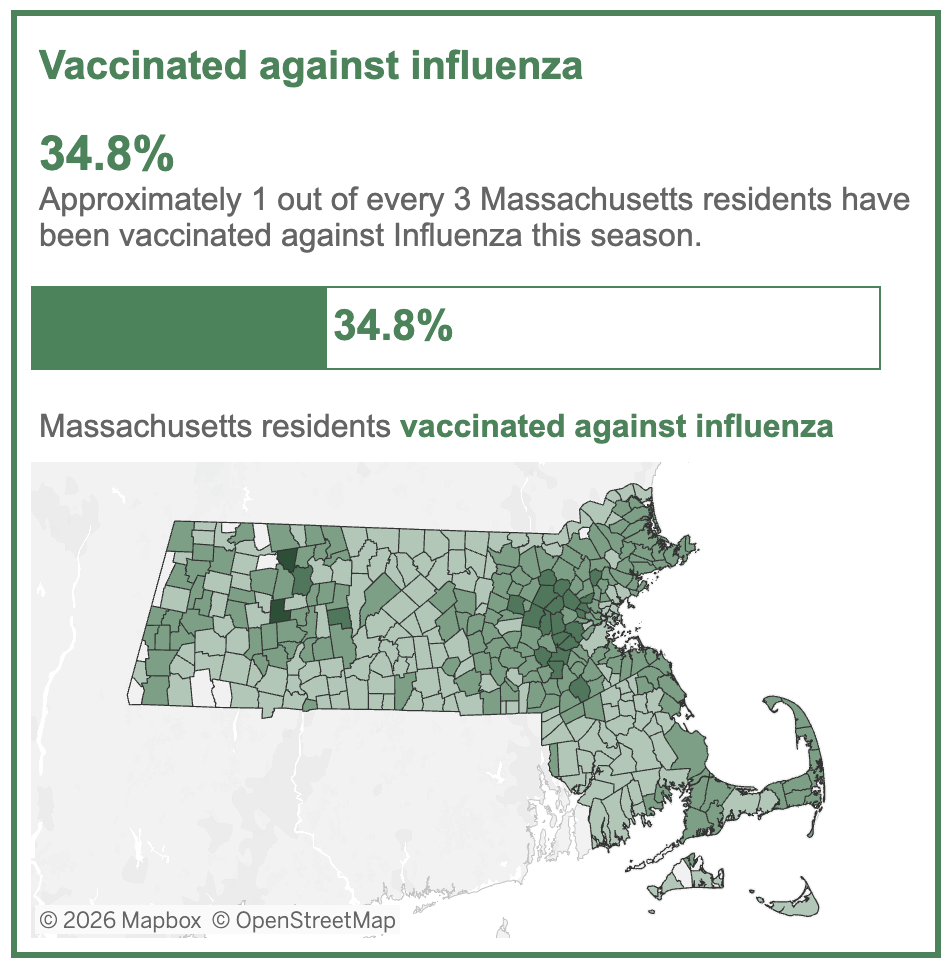

If the adverse events are transient, why does this matter? Seasonal influenza vaccination is not a one-time emergency intervention; it is an annual recommendation given to healthy children and adults alike. Despite this broad recommendation, enthusiasm for this vaccine among the public is already lukewarm at best. Here are this year’s data from Massachusetts:

Vaccines that cause more short-term side effects without clearly superior clinical benefit will be a very hard sell in the clinic, especially on a yearly basis.

A Broader Perspective

This decision and these results are particularly disappointing given what mRNA technology demonstrated in 2020 in response to Covid-19. Traditional influenza vaccine production remains slow, dependent on strain selection months in advance and, in many cases, egg-based manufacturing. In the face of a novel pandemic strain — H5N1, H7N9, or something entirely new — the ability to design and scale a matched vaccine within weeks rather than months could be transformative.

Sometimes I’m asked what keeps me up at night in the ID universe; right up there, it’s that one of these novel flu strains becomes highly transmissible, and we’re stuck with the old way of making a flu vaccine. A formal review by the FDA of the Moderna data might have clarified a regulatory pathway for rapid approval of a strain-matched vaccine in the event of a pandemic.

One hopes that a formal review of the data ultimately occurs, with pandemic preparedness in mind.

(Addendum: The day after this posted, the FDA agreed to review Moderna’s study.)

February 12th, 2026

Sometimes You Just Need to Get Input from a Real Human Being

If you’re not using AI in clinical medicine yet, allow me to strongly recommend you start — soon. Like now. It’s a phenomenal tool for looking things up quickly. I’d call it the future of information retrieval, but that future has already arrived.

If you’re not using AI in clinical medicine yet, allow me to strongly recommend you start — soon. Like now. It’s a phenomenal tool for looking things up quickly. I’d call it the future of information retrieval, but that future has already arrived.

OpenEvidence is currently leading the pack, at least around here. Doximity is close behind, with its slick suite of patient communication tools — HIPAA-compliant Dialer, video visits, even free faxing (still sometimes necessary, unbelievably). Doximity’s note-generating feature is increasingly popular as well. Even UpToDate is entering the arena; their AI is in beta, and what I’ve seen so far is genuinely impressive.

And of course, that doesn’t even touch the broader AI ecosystem — ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini — which our patients are already using in droves.

But as I’ve written before, AI has its limits. It is exceptionally good at summarizing consensus guidelines, but less good at navigating the messy gray zones where guidelines don’t quite apply. And as anyone caring for real patients in real hospitals and clinics knows, those gray zones are often where the hardest decisions live.

That’s where input from real people becomes essential. Below are a few existing and emerging strategies we ID doctors use when the question isn’t just “What do the guidelines say?” but rather, “What would you actually do?”

I’m deliberately setting aside the site formerly known as Twitter — and the somewhat less entertaining, differently annoying Bluesky — since those well-worn platforms have already been extensively discussed elsewhere.

A Listserv

Let’s start with the oldest technology of the bunch — a listserv. If that word makes you nostalgic, you know what I’m talking about. If not, think “reply all,” but with thousands of people with similar interests.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) maintains a members-only listserv, and nearly every ID doctor in the country seems to be on it. (It’s not just ID docs; most professional societies have one.) When someone posts a clinical question, responses roll in — bundled into a single daily email rather than flooding your inbox one by one (mercifully).

Posting a truly difficult case there can be quite helpful. With a patient’s permission — and full transparency that the “audience” would be other ID physicians and pharmacists — I once shared the details of his extraordinarily difficult-to-treat infection. Within a day, I had multiple thoughtful responses from clinicians who had faced almost the exact same scenario. The cumulative wisdom of that group was impressive.

The drawbacks are predictable. The interface is clunky. Good luck finding archived discussions on the IDSA website. And not every thread is about patient care. Longtime members will recall the spirited debate over whether our journals should arrive wrapped in plastic — a topic that dominated the listserv for weeks.

And of course, participation is voluntary, which means extroverts dominate the discussions. Which, come to think of it, is true of most human discourse.

TheMednet

This online forum of tricky clinical questions has been around for years. It was started in 2014 by Dr. Nadine Housri, a radiation oncologist, and her brother Samir when they were looking for answers about their father’s diagnosis of prostate cancer. Originally focused on oncology, it now covers multiple specialties.

But it was completely unknown to me until recently, probably because the ID community didn’t launch until 2024. (Thanks to their ID editor, Dr. Patrick Passarelli, for this inside information.) The questions they post, and the responses they receive are both relevant and at times quite helpful, if only to show the diversity of clinical practice when guidelines won’t cut it. Confess it’s surprised me how genuine the questions are to day-to-day practice.

Here are a few examples (login required):

In light of recent measles outbreaks in the US, would you recommend an MMR booster for immunocompetent patients born before 1957?

Do you recommend a prolonged duration of antibiotics and/or suppression for patients without pre-existing hardware who have placement of new hardware after decompression/washout of Staph aureus epidural abscess?

What is your preferred third antimicrobial agent for a patient with treatment-naive pulmonary MAC without cavitary disease and strict contraindications to utilization of rifampin or rifabutin?

Great stuff, right? You can tell these questions are generated by actual ID doctors in practice, which makes them so real. Often there is no “right” answer, but that’s the point! If these emails are getting screened out by your spam filter, you might want to give them permission to enter your inbox for a while and see what you think. And for you AI gurus out there, these are terrific queries to challenge your large language models.

Roon

If the IDSA Listserv represents the early internet and theMednet feels like a curated collection of tough clinical questions, then Roon is something else entirely — a new, physicians-only social network that’s trying to make medical Twitter good again. Only clinicians with verified NPI numbers can join, which immediately changes the tone. No anonymous nasties. No bots. No performative outrage. Just doctors talking to other doctors.

Full disclosure: I know one of the physicians behind Roon (a cardiologist), and have been following the platform with interest since he reached out to me. It’s very much still early days, with a slowly growing community and only a partial launch in most specialties. In other words, it hasn’t fully found its rhythm yet. But just the fact that Dr. Anthony Breu signed up is reason alone to give it a try. He’s the author of some of the most fascinating medical Twitter posts in history, threads so successful that he even landed a piece in the august pages of the New England Journal of Medicine!

If the Roon people want my advice, here it is: broaden your reach to include clinicians worldwide, expand beyond physicians (pharmacists, nurses, PAs), and look carefully at the graphic capabilities of existing platforms. Seeing images, figures, and videos from clinical studies is what made ID Twitter live, and made it fun.

I’m sure there are other platforms offering similar clinician-to-clinician advice; if so, let me know what you’re using in the comments. AI is already remarkably good at telling us what the guidelines say. But when the guidelines don’t quite apply, I suspect the next step — ironically — may be something rather old-fashioned.

Asking a real human being.

February 4th, 2026

Mystifying Abbreviations — Infectious Diseases Edition

Motivated by an attending stint on the general medical service, I once wrote a post here called, “Mystifying Abbreviations on Medical Rounds.” It proved to be quite popular, so I’m pleased to inform you that saying “RUQUS” (right upper quality ultrasound) and “G and G” (glucan and galactomannan) have truly entered the vernacular, especially here at my hospital.

(I’m convinced we remain the #1 utilizers of beta glucan testing in the world, for better and for worse. The low-risk case with the barely positive beta glucan triggers a spectacular number of unnecessary ID consults.)

Now, I’m back with a similar topic, only this time with an ID-specialty focus. My inspiration this time wasn’t the inpatient medical service, but an email a colleague wrote that truly stretched the limitations of my acronym knowledge. I found myself re-reading several sentences, wondering “huh?” and “what the …?” multiple times, not able to decipher their meaning even within the context of the email.

Here, for the record, is part of that email:

RCTs on provision of SUD tx with PrEP and ART like MHUs and PNs — RCT just completed NIDA funded, CROI abstract to come … also LAI PrEP and ART plus SUD tx to PWUD …

So here’s the challenge: I’ve listed a bunch of ID-related acronyms below and made brief comments that sometimes are hints — and other times are just the first thing that popped into my head. You, the wise readers, will offer your suggestions about what they mean. Some should be easy, some might be truly head-scratchers, but that’s part of the fun.

Have at it.

IGRA — frequently ordered, almost as frequently misinterpreted

PWID — very similar to PWUD, but somehow different enough to justify a separate acronym

BSI — not to be confused with BSA

CLABSI — BSI, but now with administrative consequences

CRBSI — similar to CLABSI, but until recently, I hadn’t heard this one so including it here

DILI — sounds cute; very much not

VRE — a three-letter word that can force you stop citalopram

CRE — looks like VRE, behaves worse

CPE — related to CRE, but more specific

ESBL — aspires to be pronounced as a word like MRSA instead of letter-by-letter, which it always is

PSSA — say this one it as it’s written and you too can sound like you’re from South Boston

LAI — add it to your coffee in the morning

MDR — vague, ominous, and highly contextual

XDR — MDR, but worse

RIPE — not for XDR

BCx — the lowercase “x” at the end is different from the X in XDR, and stands for … nothing, though UCx uses it too

PDR — RRRRRR, or “pirate bacteria”

SUD — encompasses OUD, AUD, and StUD — and you know what those are, right?

TDM — sounds straightforward until you need to interpret and act on the results

EHE — bold vision, weird acronym

IRIS — pretty name, not so pretty to manage

LTBI — may need RIPE “lite,” and importantly non-infectious

PsA — no one can explain why the third letter is capitalized

bNAbs — another one with inscrutable capitalization rules — I mean, why not BNAbs?

TOC — beware lingering molecules of dead bugs!

OPAT — does not refer to Irish people named “Patrick”

EOT — you’ll suffer if you don’t specify this for your OPAT patients, those named Patrick or otherwise

AYALHIV — well, I know what the last three letters stand for

Of course, abbreviations and acronyms exist for a reason — they save time, space, and keystrokes, and they let us sound efficient while we’re still figuring things out. But when they pile up unchecked, they turn even a straightforward clinical discussion into something that feels like a badly encrypted message, or that 6-character jumble (the confirmation code) that you get with every flight. People are well within their rights to say, on hearing a new one, what does that mean?

Before wrapping up, here’s one of the more absurd abbreviation sagas in modern medical history. For years, we’ve been required to check off “GC modifier” on every patient we see with a trainee in order to get credit for their documentation. Fine.

But no one — and I mean no one — knows what “GC” actually stands for. Not physicians. Not coders. Not compliance officers. It exists solely as two letters that must be clicked, lest the visit somehow not count. Which may be the purest example of an acronym achieving total bureaucratic independence from meaning — and a fitting way to end a discussion about how shorthand, once created, takes on a life of its own.

January 27th, 2026

Florida Moves to Cut AIDS Drug Assistance Program — and Drops the Most Prescribed HIV Regimen in the Country

We prescribers of HIV medications — and our patients — have for the most part lived in a very privileged space in this country. Newer drugs with advantages in efficacy, safety, or convenience have generally been covered, either by private insurance or by government drug-assistance programs.

We prescribers of HIV medications — and our patients — have for the most part lived in a very privileged space in this country. Newer drugs with advantages in efficacy, safety, or convenience have generally been covered, either by private insurance or by government drug-assistance programs.

Drug coverage was historically so good that it even got the pole position in this blog; it was the topic of the very first post! In it, I half-sarcastically advised that the rest of our chaotic health care system adopt the same approach to drug benefits. What a simple solution, ha ha.

But I’ve been in this field long enough to know that this implicit assumption (“all HIV meds are covered”) was never going to last forever. And indeed, over the years, payers have applied increasingly close scrutiny to the high cost of antiretroviral therapy, sometimes by limiting choices, and sometimes — far worse — by proposing “alternatives” that are medically inappropriate or even dangerous.

If you’d like an example of the latter, and can tolerate a brief detour into my own wrath: one payer that refused to cover doravirine suggested efavirenz, rilpivirine, or nevirapine (!) as substitutes — despite the patient having already experienced intolerable side effects on efavirenz, and having clear contraindications to the latter two. In other words, the recommendation was not merely unhelpful, but truly dreadful.

As a result, over time we increasingly hear from patients that their well-tolerated, effective regimen is no longer covered. More commonly, it remains technically “covered,” but only with a punitive medication co-pay — which, as I’ve written before, is an irritating euphemism for the same outcome. Co-pay really means: You pay, not your insurance.

Our patients’ response to all this disruption? They hate it, of course — not just because of the cost, but because changing a stable HIV regimen reopens anxieties many thought they’d left behind.

Which brings us to Florida — a southern state with a large population of people with HIV, including several urban areas with among the highest HIV incidence rates in the country. Until recently, Florida had an extraordinarily generous AIDS Drug Assistance Program (or ADAP). An experienced HIV provider described the program to me as: “Honestly kind of crazy. I love it!” The formulary covered pretty much everything, including some truly high-ticket items.

But just announced were major cuts. What makes this different from the usual commercial insurance shenanigans is that ADAPs (or here in Massachusetts, HDAPs) function as the safety net for people with no other means to pay.

The most visible headline is a reduction in income eligibility, from 400% to 130% of the Federal Poverty Level — a substantial drop, and it’s not clear how those patients will now access lifesaving medications. Another major change affects the ADAP formulary itself. Most notably, Biktarvy will no longer be covered.

Excuse the one-time brand-name mention, but otherwise I’d have to write bictegravir-emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide (!!!), or BIC/FTC/TAF, or BF-TAF (all mean the same thing). Importantly, the state has indicated that “all other current antiretroviral medications,” including dolutegravir (Tivicay), will remain available.

For non-HIV treaters still reading, here’s some context: not covering BIC/FTC/TAF is like Shake Shack announcing it won’t be offering burgers and fries. You can still get a meal — just not the thing you’ve been ordering for years.

Indeed, this change is noteworthy because BIC/FTC/TAF is currently the most commonly prescribed HIV treatment in the United States. It is highly effective, well tolerated, simple, has few drug interactions, carries a low risk of resistance, and provides hepatitis B coverage. One of our recent fellowship graduates joked that learning other HIV regimens wasn’t worth the effort, since nearly everyone could just take BIC/FTC/TAF. While HIV experts may bristle at this oversimplification — our extensive ART knowledge demeaned! — there is, admittedly, some truth to it.

So what to do when BIC/FTC/TAF is no longer an option?

Because dolutegravir remains covered, one obvious alternative is to build regimens around this highly potent integrase inhibitor, which is very similar to bictegravir. The two-drug combination of dolutegravir-lamivudine would be the best option for most patients, especially if the branded coformulation (Dovato) is covered — it’s just exchanging one pill for another. If it’s not covered (the price in many states is similar to BIC/FTC/TAF) and the goal is cost-cutting, then the two-pill regimen of dolutegravir plus the very cheap generic lamivudine would do the same thing, with somewhat less convenience.

This less expensive regimen is almost as good as BIC/FTC/TAF for appropriately selected individuals, with three important caveats:

-

It does not provide sufficient hepatitis B treatment, so it is unsuitable for people with chronic HBV infection.

-

It is not appropriate for patients with lamivudine resistance.

-

It requires taking two pills instead of one, which may matter for some patients more than others.

Another two-pill option is dolutegravir plus generic TDF/FTC, which retains hepatitis B activity and remains a familiar, guideline-supported regimen. The tradeoff here, of course, is the renal and bone toxicity associated with TDF, making it a less attractive choice for older patients or those with underlying kidney disease. TAF/FTC (brand name: Descovy) will reportedly be available only to individuals with reduced renal function.

The trigger for these changes is unsurprisingly budget pressure, attributed to rising health-insurance premiums nationwide and the absence of additional Ryan White funding. Those of us who prescribe HIV therapy should expect to see more of these cost-containment efforts from both private and government payers in the years ahead.

In that sense, Florida’s ADAP decision may be a harbinger of what I’ll call the looming statinification of antiretroviral therapy: a future in which payers mandate generic regimens unless there are clear contraindications. (And I’ll drop a patent on that word used in this context, so all future revenues derived from its use will flow to this blog.)

But here’s an important reminder: Just because something saves money doesn’t mean it will be welcomed by all — or that it will come without consequences, both good and bad. Let’s see how this unfolds, as apparently another large southern state is watching the Florida experience closely.

I wonder what that could be.

January 21st, 2026

Rabies Is Terrifying — and the Challenge of Managing a Low Risk of a Dreadful Disease

Three case reports of human rabies recently appeared in the MMWR. Reading each one served as a reminder of just how horrifying this infection is when it strikes — which very fortunately is quite rare in our country.

Two cases were domestic and followed recognized direct bat exposures with no post-exposure preventive measures taken. Here are the exposure summaries:

Case 1: In July 2024, a Minnesota woman who lived alone reported to family members that a bat or bird had been trapped in her house for several days. After discovering a bat in the sink, she reportedly killed it with a hammer and disposed of it. A bite was not mentioned; however, the method reportedly used to kill the bat could have produced splatter resulting in inoculation of infectious nervous tissue onto broken skin or mucous membranes. In addition, family members reported that the patient wore a hearing aid, was a deep sleeper who used a continuous positive airway pressure machine, and routinely consumed alcohol, factors that might have reduced her awareness of having had direct bat contact.

Case 2: In October 2024, a woman living in California told family members that she had recently found a bat indoors at her worksite. Although the bat initially appeared to be dead, when she handled it with her bare hands, she felt movement and a possible bite. She discarded the bat, and in the absence of any apparent wound, did not consult a medical provider or public health officials, and the bat was not tested for rabies.

Symptom onset was 3 weeks after bat exposure in the first case and 1 month in the second. Both individuals died.

The discussion emphasized the importance of the CDC’s recommendation to give the rabies vaccine after any direct bat contact. North American bats are small, and bites might not be apparent, causing trivial injuries. This is especially critical when the patient has conditions that make them less likely to notice a bite, as in the first case. As a result, any direct contact with a bat should warrant preventive intervention.

The third case was imported, with the patient’s exposure in Haiti 7 months before clinical presentation. (You read that right.) A prolonged delay in diagnosis led to a large number of healthcare workers potentially exposed, though fortunately none developed rabies. After a 10-day hospitalization at one hospital, he was transferred to another where the diagnosis was ultimately confirmed; he died approximately 6 weeks after initial symptom onset.

Key to solving the origin of this case was the phylogenetic analysis of the patient’s rabies virus, which showed it derived from a strain known to be endemic in canines and wild mongooses in Haiti — and distinct from the bat variant most commonly identified in U.S. cases.

These cases serve as a reminder that rabies remains an almost universally fatal condition. A case report of a 15-year-old girl who survived has led to some adoption of the treatment she received — the “Milwaukee Protocol” — though there is debate about its specific effectiveness versus advances in the critical care of patients with coma. Regardless, even survivors often have serious neurological sequelae — this is a terrible disease.

The challenge for us clinicians here in the United States, with only a few cases reported annually, is to assess the risk of exposures in scenarios quite different from those outlined in these recent case reports. We’d all recommend post-exposure prophylaxis and vaccination for patients who directly handled a bat or were bitten by a dog in Haiti.

But what about the bat flying around the house, or in a garage, but with no apparent bite? Canada dropped recommending rabies preventive measures for that scenario, with no reported increase in rabies cases. Or a dog bite in a foreign country with an established rabies vaccine protocol for dogs?

Consider the following cases:

Case 1: A man awoke from a sound sleep to find a bat flying around his room. He opened his windows and left the room. He returned in an hour, and the bat was gone. There was no apparent contact with the bat.

Case 2: A 12-year-old boy sustained a dog bite from a neighbor’s dog while visiting family in rural Brazil. The bite occurred while they were playing with a tennis ball, breaking his skin and causing slight bleeding. The neighbors said the dog had received most of its scheduled rabies vaccines and had exhibited no abnormal behavior.

Go ahead and vote! And let’s hear your thoughts in the comments section!

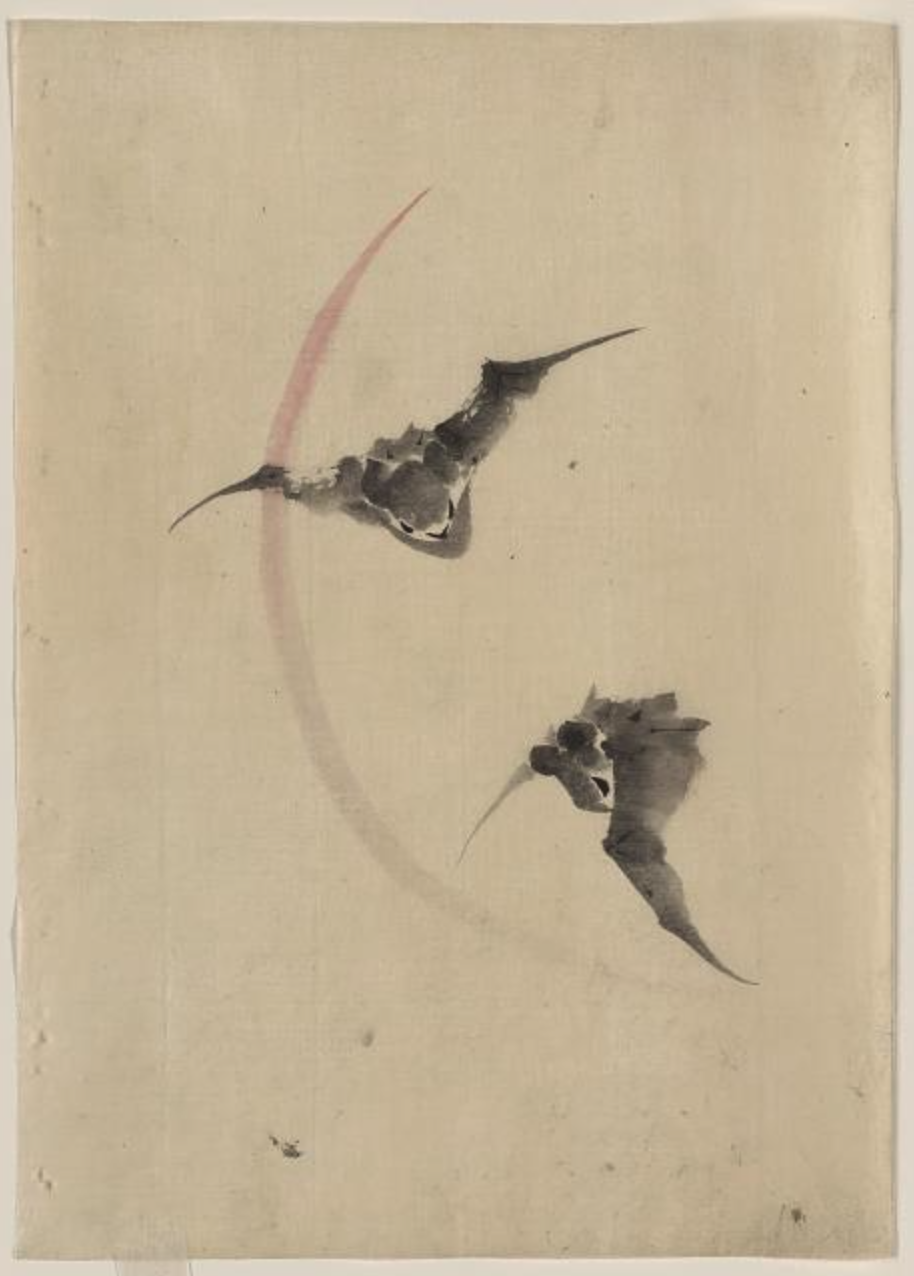

(Image: Two Bats Flying, by Hokusai Katsushika, 1830. National Library of Congress.)

January 14th, 2026

Influenza — So Familiar, Still So Mysterious

In what feels like the fastest-peaking influenza season in quite some time, I find myself returning to a familiar answer when asked questions about this miserable virus: “We just don’t know.”

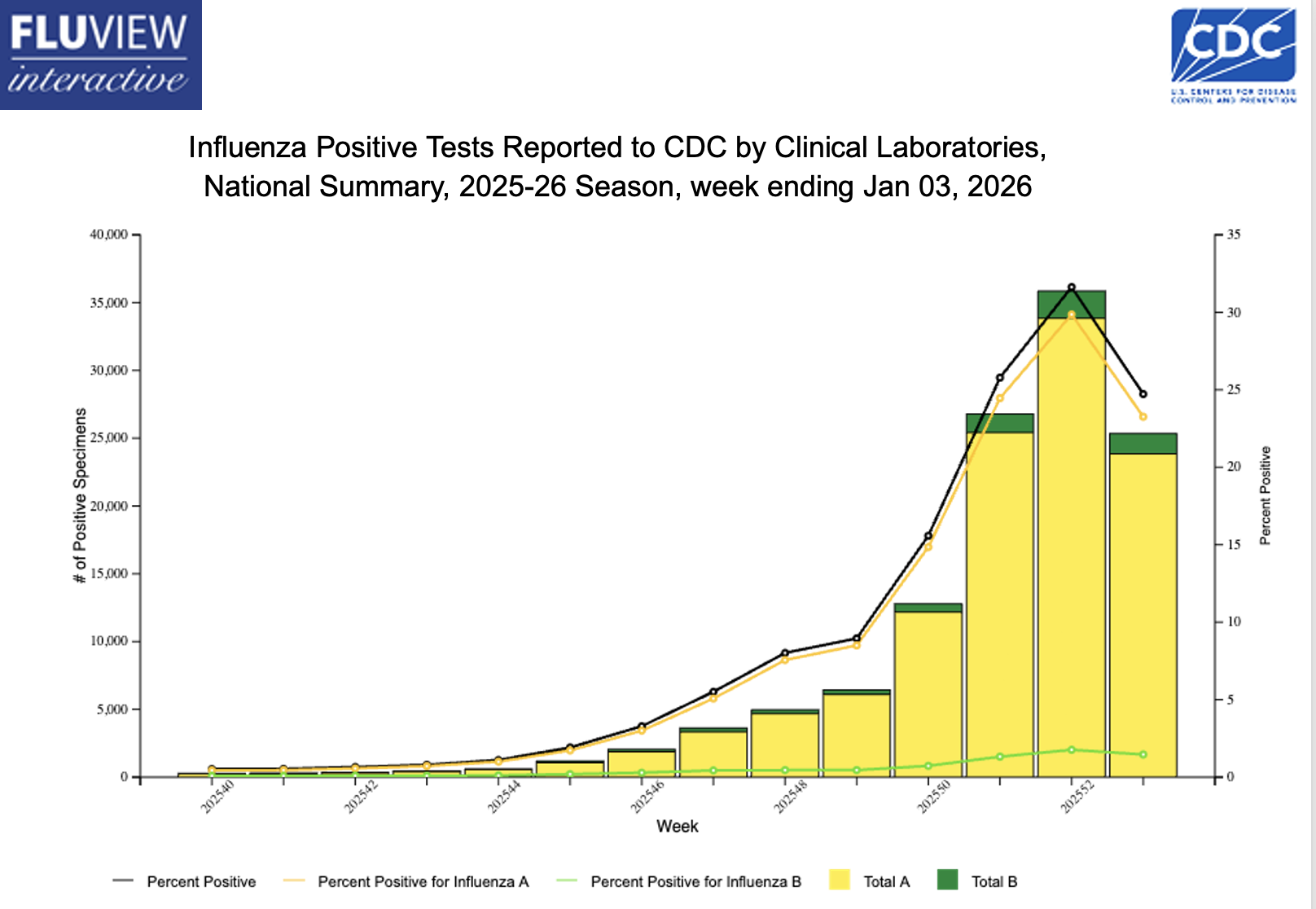

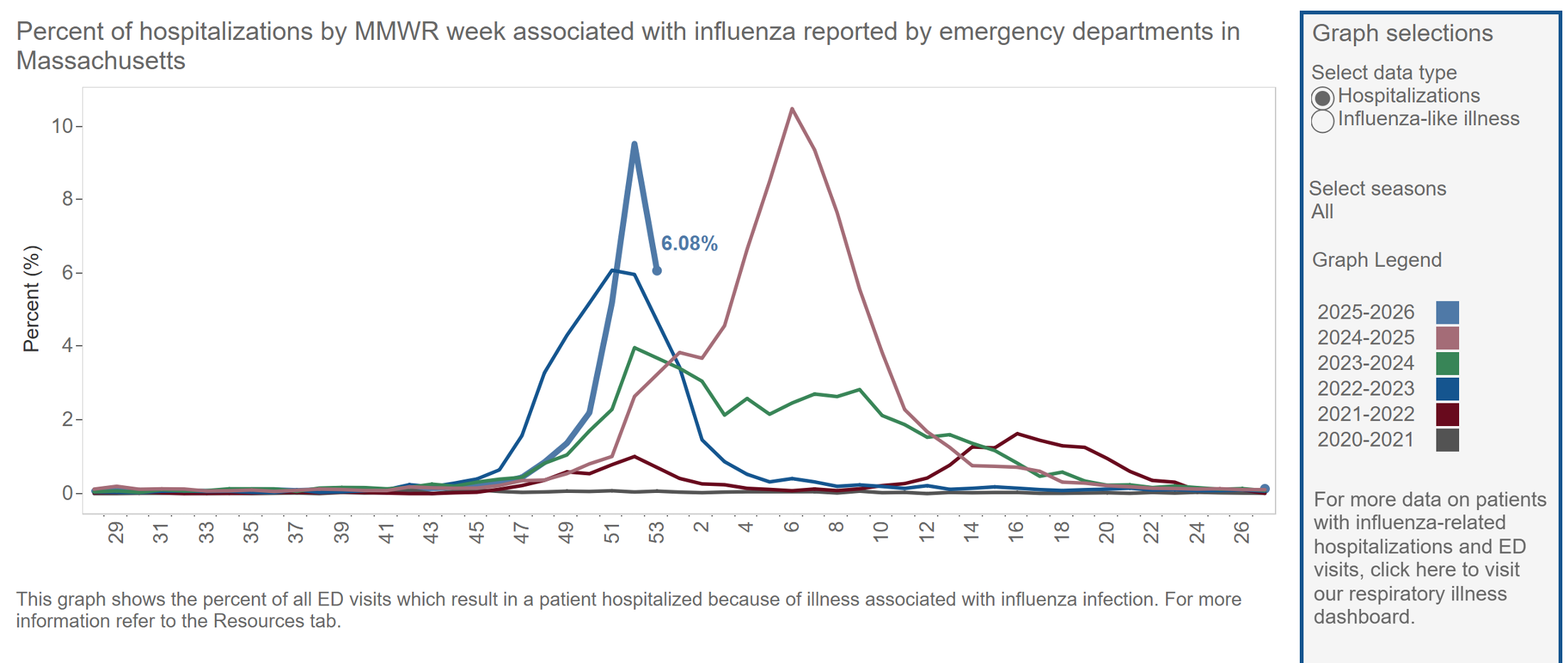

At least I hope it’s peaking — take a look at this encouraging recent trend:

Decline notwithstanding, there’s still tons of influenza activity out there, triggering the usual flurry of questions from patients, friends, colleagues, and the media. I’ll share a bunch of these common questions, along with my best attempt at answering them.

#1: Why do some influenza seasons start quickly, while others don’t get going until later in the winter?

Weather is one common explanation, as temperature and humidity are the most significant meteorological indicators associated with epidemic onset (cold and dry are worse), and their effects vary by influenza subtype — but it seems particularly important with H3N2, this year’s dominant strain. Certainly it’s easy to point at our unseasonably cold December here in the Northeast as the culprit, but it’s not just that.

In fact, the most common explanation this year is the emergence of the dominant H3N2 subclade K (from J). I’ll confess that until recently I didn’t even know influenza had “subclades,” but any viral change that weakens existing immunity can plausibly increase case counts.

Even worse is when there’s a more dramatic shift. Remember 2009? A new influenza A (H1N1) virus, nicknamed “swine flu,” emerged and rapidly spread globally. It caused the first influenza pandemic in over 40 years, including tons of spring and summer cases (that off-season surge was so bizarre), and disproportionately affected children and teens.

H3N2 subclade K isn’t that kind of change, fortunately. To what extent it (vs. the sustained cold weather) explains the intense early flu activity is unclear.

#2: Does the early start to the flu season mean it’s going to be like this the whole winter?

Headlines everywhere the past several weeks blared that we were experiencing the worst flu season in years. Sure, it was a particularly severe start, but the time of onset and duration of the season are separate issues. A season that starts early may end quickly (fingers crossed); another may start and peak later, then smolder for months — the latter is what happened last year, which was a very bad flu season, and which didn’t peak until February.

Some years the long duration of the flu season is attributed to a shift from predominantly influenza A to influenza B; this can also give some unfortunate individuals a second case of flu in the same season. As before, whether this will happen in 2026 is another “we don’t know” reality.

In summary, a season that starts out raging might not ultimately be severe in aggregate. This fact is much less newsworthy, so it doesn’t get the headlines.

#3. Why are we still so bad at predicting dominant circulating strains?

Surveillance is inherently backward-looking. We take a look at the global circulating strains and make a best guess what will hit us, what to put in the vaccine, and what to expect. But viral evolution is unpredictable, so this year’s K subclade isn’t in the vaccine.

In hindsight, the dominant strain can sometimes seem obvious, but in reality, it rarely is.

#4: When there’s crazy flu activity like this, why doesn’t everyone get sick?

Another way of asking this question — why is the household attack rate of influenza only approximately 15-20%? After all, these are people sharing the same room, the same air, the same surfaces as an active case of the flu. If we had a better understanding of host susceptibility, we’d be much better at instituting preventive strategies, like postexposure prophylaxis with oseltamivir or baloxavir.

Take a look at this recently published study for how mysterious transmission is for this winter scourge: Researchers brought naturally infected “donors” (with confirmed active influenza) together with healthy “recipients” in a controlled hotel/quarantine setup, sampled air and surfaces, and yet not a single recipient developed influenza by symptoms, PCR testing, or serology.

A bunch of theories have been posited by one of the researchers, including protective immunity among the volunteers and sparse coughing by the donors, but here’s what I want to know: where can I find a hotel that completely blocks influenza transmission — and can hospitals learn anything from it?

(That was a joke.)

I have a query in to a coauthor what the stipend was for participating as a “recipient” — hope it was generous!

#5: Is the reason for such intense flu activity all the negative messaging about vaccines?

Despite the universal recommendation to give the flu vaccine each year, this year most people have chosen not to do so. Here are data from Massachusetts:

But I’d be skeptical of claims that the rapid start to this year’s flu season was driven by low vaccine uptake. First, it’s no secret that this is not a popular vaccine; even in “good” years for flu vaccine uptake, only half the population chooses to get it. Second, the vaccine has never been great at preventing infection, so it’s not clear to what extent this would play a role for a year where the major circulating strain isn’t even in the vaccine.

Important reminder: studies consistently show an association between getting the flu vaccine and a reduction in severity. hospitalizations, and deaths — and that even seems to be the case in early data from the U.K. involving H3N2 subclade K, especially in children. Get the vaccine, it’s not too late!

Five questions, five variations on “we really don’t know.” Influenza has been with us for millennia and studied intensively for decades, yet it continues to surprise, confound, and humble us. Perhaps that uncertainty is itself the most reliable feature of this most familiar winter virus.

January 6th, 2026

How the Z-Pak Took Over Outpatient Medicine, Part 2: The Reckoning

Part 1 of this azithromycin series explained how the drug became ubiquitous. In Part 2, we’ll explore why many of us infectious diseases physicians now groan when they hear the words, “They already started a Z-Pak.” Because what began as a genuine pharmacologic advance became, through sheer volume of use, an antibiotic that doesn’t work very well, yet can still cause side effects and muddy diagnostic waters (and cause groans).

Here are the problems — some specific to azithromycin itself, and some due mostly to its sheer popularity, because otherwise these problems are shared with any indiscriminate use of outpatient antibiotics.

Please stick around to the end, because I’ll finish with some clinical indications for azithromycin where it remains arguably the drug of choice.

Bacterial Resistance, or The Bugs are Smarter Than We Are

The biggest problem with azithromycin overuse is also the most obvious: resistance, which emerged quickly among common respiratory pathogens. Macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae is now widespread, with rates in many regions high enough to make empiric use difficult to justify. Resistance in Haemophilus influenzae is lower but has also increased steadily over time.

Even Mycoplasma pneumoniae — once reliably susceptible — has developed striking resistance in parts of Asia, where 80–90% of isolates are now macrolide resistant.

And Streptococcus pyogenes, the cause of strep throat, is no longer consistently treated with macrolides. Azithromycin susceptibility is unpredictable, with resistance rates varying widely by region and occasionally rising with alarming speed. Since most clinical sites don’t do routine susceptibilities on strep, it’s a guessing game whether azithromycin will work for this indication.

Notably, this shift has already been reflected in practice guidelines. Major recommendations for outpatient respiratory infections have steadily moved away from macrolide monotherapy in most settings — an acknowledgment that resistance has eroded azithromycin’s reliability for empiric treatment.

Induction of Culture Negativity

Is that the right term? Here’s the scenario, you decide:

A 75-year-old man with a history of aortic valve replacement starts feeling tired. Shortly thereafter, he notes a little low-grade fever and loss of appetite. He’s convinced he’s coming down with something because he’d just spent a busy holiday weekend with his three grandchildren — toddler twins and a 5-year-old in daycare, all of whom have some sort of respiratory crud.

So he dials up his favorite online telehealth service, gives the above history including the three sniffly, coughing kids, receives a prescription for a Z-Pak, and clicks the 5 (out of 5) rating for user feedback before signing off.

The problem? This illness could well be bacterial endocarditis, commonly caused by strep and staph, many of which are susceptible to azithromycin. A few days of empiric treatment is just enough to turn blood cultures negative, but clearly not sufficient for treatment.

So if you wonder why we ID doctors groan at the “already started a Z-Pak” history, one reason is that culture-negative endocarditis — and related “culture-negative” cases — are some of our most challenging ID consults.

Diagnostic Confusion or Misdirection

The most common issue is that someone gets a viral respiratory tract infection, gets a Z-Pak, gets better, and assumes it was the antibiotic that did it. In the minds of some of our patients, that’s a powerful reinforcement loop that no randomized trial can ever fully undo.

Which reminds me to emphasize that there has been a double-blind, clinical trial of azithromycin (vs. vitamin C) in outpatient bronchitis. Take a look at one of the most important endpoints, “Proportion of patients who had returned to their usual daily activities.”

If you prefer the result in movie comedy form, this is for you:

That’s right, nearly (but not quite) identical — in statistical terms, we call this “not significant”.

A different problem arises with Fusobacterium necrophorum, the bug with a scary name and the most common cause of septic jugular vein thrombosis, or the dreaded Lemierre’s syndrome. Occurring predominantly in teens and young adults, Lemierre’s can take a previously healthy kid and put them in an ICU with critical illness — and azithromycin isn’t active against F. necrophorum, while beta-lactam antibiotics have excellent activity. This can lead to a dangerous delay in diagnosis.

Here’s how the story typically unfolds:

- 19-year-old college student with a vague history of penicillin allergy goes to university health service with a bad sore throat.

- Rapid strep negative; told to go home and rest, it’s a viral URI. [Important note: This may well be true at the outset!]

- They come back with worse symptoms. Work-up for mono negative.

- Empiric azithromycin prescribed, not penicillin or cephalexin, because of that penicillin allergy.

- Waits a few days to see if the azithromycin works, but develops even higher fever, neck and chest pain, shortness of breath.

- Goes to emergency room where evaluation shows jugular vein thrombosis and septic pulmonary emboli.

- Blood cultures grow Fusobacterium necrophorum, less commonly other oral bacteria.

- Experiences a prolonged hospital stay requiring intravenous antibiotics, anticoagulation, and sometimes further complications.

As I said, scary. Admittedly, it’s rare, but Lemierre’s definitely happens; azithromycin isn’t the culprit, but it can act as a prelude to delay diagnosis and the start of effective therapy.

Side Effects

All antibiotics have gastrointestinal side effects by altering the normal microbiome. But macrolide antibiotics, even azithromycin, act as agonists on the intestinal peptide motilin to stimulate gut activity, which can cause cramping and diarrhea. Little-known fact — this off-target prokinetic effect means erythromycin (remember that?) can be used as a treatment of gastroparesis and select cases of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

QT prolongation is another signature side effect of macrolide antibiotics. While azithromycin has the lowest tendency, it remains a problem in particular for patients taking other QT-prolonging agents and those with underlying cardiac conduction disorders. And some (but not all) population-based studies have linked azithromycin use to an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

All Right, Enough Already — When Should We Use Azithromycin?

Despite all of the above, azithromycin remains an important antibiotic when used for the right indications. There are several settings in which azithromycin remains clearly useful, and in some cases essential.

- Azithromycin continues to play an important role in the treatment of certain sexually transmitted infections, either as first-line therapy or as part of combination regimens, depending on the pathogen and local resistance patterns.

- Azithromycin remains a key agent for infections caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae when susceptibility can reasonably be assumed, particularly outside regions where macrolide resistance is now common. It’s why we still see it as part of combination therapy for people admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia, as it also has activity against Legionella species and Chlamydia pneumoniae — and beta-lactams don’t.

- Most critically, azithromycin is indispensable in the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infections, especially Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and Mycobacterium abscessus. The distinction between macrolide-susceptible and macrolide-resistant isolates carries enormous prognostic significance.

Ok, I’m done now — enough about azithromycin, good and bad. Hope you enjoyed this journey! Reminds me of the ID doctor who started their note with “Briefly, …” and then went on for 2000 words. (Actually, over 2500.)

We can’t help ourselves!

And thanks to Dr. Ryan Christianson, who alerted me to this television commercial, which amazingly sponsored Sesame Street in 2001.

(Source of zebra image at top: PublicDomainPictures.net)

December 29th, 2025

How the Z-Pak Took Over Outpatient Medicine

Chances are, across this great land of ours, right at this very moment, someone is coughing, or sneezing, or struggling with a sore throat, or some combination of the above, and taking the antibiotic azithromycin. Or they might be just fevering, with no discernible cause, and still they’re taking azithromycin.

They might have obtained it from an urgent care clinician, an online telehealth service, a supply they had stashed away “just in case,” or any number of sources that most likely didn’t assess whether the benefit of taking the antibiotic outweighed the risk.

Here’s the thing — there’s a very high likelihood it’s doing them no good at all, and there are a bunch of reasons why it might actually be harmful. As an example, more than a decade ago, I wrote about data linking azithromycin to increased cardiovascular events.

Before we get to this and other problems with azithromycin (Part 2 — it’s coming!), let’s take a look back at the history of this extremely popular antibiotic and how it achieved its pre-eminent position in outpatient medicine.

Erythromycin: An Antibiotic That Packed a Punch (to the Gut)

Back during the Ronald Reagan years, the macrolide antibiotic erythromycin was the leading alternative to penicillin. Widely used in people with penicillin allergies — real or otherwise — erythromycin nonetheless had several disadvantages, the most important of which was an incredibly high rate of gastrointestinal side effects.

Nausea. Abdominal cramping. Diarrhea. Bleh.

Typical doses were 250 mg four times a day, or 333 mg three times daily, often prescribed for a week or even longer. The thrice-daily 333 mg dose was more convenient, and supposedly better tolerated, but frankly sparing that 1 mg/day didn’t do much to reduce its side effects.

True story — my first attending physician in a medical school hospital rotation was a gastroenterologist. He’d come down with the sniffles, and he told us he started himself on erythromycin “just in case” (second time I’m using that phrase).

A couple of days later, he didn’t look so great — all pale and sweaty. Trying to be compassionate, I asked how he was feeling. His response: “The cold is better but the nausea from the erythromycin is a killer.”

Oh Physician, heal thyself! Erythromycin doesn’t treat colds!

(I did not tell him that. I was a third-year medical student.)

The New Kids on the Block: Clarithromycin and Azithromycin

Then, in 1991, with much fanfare, two new macrolides appeared on the scene — clarithromycin and azithromycin. Both promised to improve on erythromycin by treating a broader range of pathogens and, most importantly, having fewer side effects.

Hooray for both! Advertisements for Biaxin (clarithromycin) and Zithromax (azithromycin) bombarded doctors in medical journals. Paging through the latest issue of The New England Journal of Medicine or The Lancet, we might come across something like this:

Source: Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

Drug advertising back then was a huge source of revenue for medical journals — remember, this was before the internet. The makers of Biaxin and Zithromax were not shy about their new and improved versions of erythromycin, which really were objectively better in many ways.

We don’t hear much about clarithromycin anymore, and for good reason. Glossy ads notwithstanding, clarithromycin never quite delivered on its promise. It also caused GI side effects (though fewer than erythromycin), had major drug interactions, prolonged the QT interval, in some studies increased mortality — and could make food and drink taste absolutely bizarre.

The medical term for taste disturbance is dysgeusia, by the way — pronounced dis-GYOO-zee-uh, which kind of sounds like what it means. You’ll win big points among your friends if you casually drop this word into everyday conversation.

Another true story: A colleague of mine from a prestigious academic medical center in Baltimore boarded a flight to Europe and was upgraded to first class. Handed the complimentary glass of champagne, he tasted it and nearly spat it out. He insisted to the flight attendant that it was flawed and asked for a glass from a different bottle — which, to his disappointment, tasted the same.

Only later did he realize that the clarithromycin he was taking for sinusitis made everything taste like he was drinking from a rusty metal pipe.

So the real champ in the Battle of the New Macrolides was azithromycin, which had a few tricks up its sleeve that made it irresistible to clinicians and patients alike:

- It had fewer side effects than clarithromycin. None of that dysgeusia weirdness. (It’s fun to write, and to say, dysgeusia. I’ll stop doing so now, promise.)

- It had fewer drug interactions.

- It didn’t affect cardiac conduction quite as much, an important safety feature.

- Most importantly, it stuck around in the body for a very long time. The half-life of azithromycin is a stellar 68 hours (nearly 3 days)!

Pharmacologists oohed and aahed over this aspect of azithromycin, which was made even more impressive by its high concentrations within cells and tissues — where it lasted even longer than in the blood.

Enter the Z-Pak. Read on!

Z-Pak Reigns Supreme: The Rise of Azithromycin

What truly transformed azithromycin from a useful antibiotic into a cultural phenomenon was the way its pharmacology was leveraged into the first truly “short-course”

antibiotic.

Instead of the traditional antibiotic regimen (three or four pills a day for 7 to 10 days, ideally taken with food but not dairy, dispensed in an orange plastic bottle with a white cap), azithromycin came as six pre-packaged pills.

Generated by AI but trust me — it looked like this!

Here were the directions:

- Day 1: Two tablets (500 mg total) once

- Days 2 through 5: One tablet (250 mg) daily

Just six pills. Just 5 days. The Z-Pak is born!

The now-iconic Z-Pak took a concept from a pharmacokinetics lecture and turned it into something instantly graspable for clinicians and patients alike. A tidy blister pack. Clear instructions. A sense of completion. You finished it, decisively, in less than a week. For busy clinicians and busy patients, it felt like modern medicine at its best.

Marketing, of course, played a major role, most notably when the approval was broadened to include children, who got away with taking just 3 days. This is the United States of Advertising, after all! We’d expect nothing less.

At pediatric hospitals and in outpatient clinics, replicas of Max the Zebra — the drug’s mascot, “ZithroMAX”, get it? — dangled from stethoscopes. Medical journals arrived wrapped in zebra-striped covers. Branded stuffed animals appeared in exam rooms to comfort anxious children. In one particularly cringey moment, a real zebra was donated to the San Francisco Zoo by the drug’s manufacturer, and ceremonially named … Max. What else?

Patients (and their parents) loved the Z-Pak. Compared with antibiotics that came with frequent dosing and frequent side effects and difficult-to-open plastic bottles, the Z-Pak felt so efficient.

Add the rise of patient-satisfaction metrics to go along with the advertising, and a health care system increasingly optimized for speed and convenience, and azithromycin found itself perfectly positioned. It became the antibiotic people expected (and asked for by name — I want a Z-Pak!), and clinicians reached for reflexively.

That dynamic has only intensified in the modern era, particularly with the expansion of telehealth. Final “true story” of this post: During the pandemic, a physician colleague of mine shifted to doing exclusively telehealth for a large national company — a model that suited him well, allowing him to travel freely and spend time with grandchildren scattered across the country, mostly in warmer climates.

When I asked him which antibiotic he prescribed most often in these virtual encounters, his answer was instantaneous: azithromycin. In settings where the examination is limited, diagnostic testing is unavailable, and the encounter is brief, the Z-Pak becomes the path of least resistance.

That convenience helps explain how azithromycin came to dominate outpatient prescribing. Whether that dominance has come at a cost will be the subject of Part 2, despite the fact that I have already written far more words about the Z-Pak than I ever imagined possible.

(Source of vintage zebra image at top: publicdomainimages.net.)

December 17th, 2025

What Use Is the Physical Examination in Current Medical Practice?

A doctor and nurse examine children in a trailer clinic at a mobile camp in Klamath County, Oregon. Photograph by Dorothea Lange, October 1939.

A very interesting, quite scholarly perspective appeared in the NEJM last month called, “Strategies to Reinvigorate the Bedside Clinical Encounter.” Drawing plenty of attention on social media, it elicited the usual hand-wringing from clinicians who bemoaned the way modern medicine has evolved — away from direct care of patients and toward an ever-expanding reliance on technology for testing and communication.

With the hungry electronic medical record that always needs feeding, the innumerable administrative burdens placed on clinicians, and the simple fact that most doctors are paid per unit of service they document — not by time spent at the bedside or in the exam room — we simply don’t spend enough time with our patients.

Not enough time looking at them. Talking to them. Listening to them. Instead, we’re perched in front of that glowing screen, its shining flat-panel computer face named years ago by Dr. Abraham Verghese as the iPatient. Clever!

Why would more time with patients be so valuable? Because I strongly believe that there’s nothing worth more in an effective clinical encounter than taking a good history — and, if I may be so immodest, this is where we ID doctors shine. (It’s certainly not doing bedside procedures.) Since I’ve devoted a whole post to taking histories and spend a whole lot of time and energy with our ID fellows stressing the importance of history in what we do, let’s shift to another part of the direct clinical encounter, which is the physical examination (PE).

There are several opinions and perspectives about the PE that repeatedly come up in both the medical literature and in conversations with students, colleagues, and other health care professionals. Let’s take a look at five of them one at a time, starting with the beginners:

1. The Medical Student, the Learner

Wow, I’m going to have to learn how to use these new tools — stethoscope, reflex hammer, the ophthalmoscope … Each time I see a patient, I’m so nervous about doing something wrong that I can barely concentrate on what I’m seeing, feeling, or hearing … Is that an S3? A systolic or diastolic murmur? What’s the difference between rales and rhonchi — I think I know what wheezes are … Is that 1+ or 2+ edema? What is shifting dullness again? Which cranial nerve are we testing when we ask them to shrug their shoulders, and why is it a cranial nerve anyway? And can the patients tell that I have no idea what I’m doing, basically all of the time? Oh, to have the confidence of the senior resident on this rotation, who somehow always knows what and how much to do! And the attending does even less …

2. The Pediatrician, the True Believer

The physical exam is absolutely critical … especially in babies! After all, they can’t tell you what’s wrong … A parent’s intuition (usually the mom’s, let’s be honest) is helpful, but still — she’s not going to pick up hip dysplasia, or the absence of a cornea reflex, or scoliosis, or a heart murmur … My entire career is filled with these pick-ups, each a little win for early detection … I can’t imagine a clinic visit without a good physical exam … And get the clothes off, please! No one can do an exam on a screaming toddler in a snowsuit …

3. The Proud Expert of the Physical Exam (Usually but Not Always Played by an Older Cardiologist)

Hey, have a few minutes to go to the bedside? Allow me to show you how the Valsalva maneuver differentiates between hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis … And while I’m at it, listen how the handgrip exercise intensifies the mitral regurgitation murmur by increasing afterload, and note how you hear the aortic regurgitation murmur better while the patient is leaning forward and exhales fully … For my money, the hepatojugular reflux test is much better than peripheral edema assessments for volume status in chronic heart failure … And by the way, I’ve never met a patient in whom I didn’t carefully assess the neck veins … it’s just a matter of finding the perfect angle, ideal lighting, understanding the difference between the arterial and venous pulsations, and making sure you’re looking at the internal jugular waveforms, preferably while shining a light tangentially across the neck … Got that?

4. The Busy and Overworked and Beleaguered Provider at the End of the Day (We’ve All Been There)

I heard a systolic murmur … Let’s get an ECHO … because the data are really limited on the accuracy of what we hear in the office and what an ECHO shows anyway … and meanwhile, I have 10 prior approvals to complete and multiple disability forms to fill out and quality metrics to meet and in-basket messages to return and abnormal tests to follow-up on, and of course everything is required sooner rather than later … and how is this even possible in a 15-minute follow-up visit, especially when my 3:15 p.m. patient arrived at 3:45, insisting that they be seen even though I’ve double-booked my 4:00 p.m.?

5. The Orthopedic Surgeon

What’s a stethoscope?

If you want my take, I’m here to say that all of these views on the physical exam have validity — each has their place, their sound justifications. That busy doctor who moves quickly to order the ECHO? The cardiologists will get the ECHO too, even after all their fancy maneuvers. And show me an orthopedic surgeon who does a careful complete PE, listening for carotid and femoral bruits, doing a Romberg test, and percussing the liver span, and I’ll show you one who doesn’t operate often enough. A more comprehensive exam isn’t always better, despite what some old-timers say.

But clearly doing some aspects of the PE is almost always better than nothing at all — and there are two reasons why.

First, a physical exam targeted by the patient history can be immensely valuable. As an example, a memorable pick-up was thanks to a resident rotating with me in ID clinic. In seeing a patient in follow-up while he was still on intravenous antibiotics for endocarditis, she heard the murmur of aortic insufficiency while doing a careful cardiac exam. After confirming her findings, and noting that they were new since discharge, I contacted his cardiology and cardiac surgery teams who were understandably alarmed; they expedited his lifesaving valve-replacement surgery.

(She’s now a cardiologist, of course. You can be sure I sang her praises and cited this case when she was applying.)

Second, most patients want us to do them. One of my current colleagues, Dr. Mary Montgomery, was an ID fellow here a bit over a decade ago. Observing her physical exams, I noted she always looked in her patient’s ears, even when they had no ear complaints. When I asked her why, she said:

I remember hearing that patients don’t feel that they are having a complete exam unless their ears are checked. So I try to look in everyone’s ears. Takes me a minute at most, so why not?

Sounds good to me!

Happy holidays, all!

(H/T Drs. Sonja Solomon, Beret Amundson, and Mary Montgomery, all three of them graduate Chief Medical Residents, for helpful feedback on drafts of this post.)

December 10th, 2025

Dengue, Malaria, HIV Cure, and Others — First Cold Snap of the Winter ID Link-o-Rama

Absolutely brutal temperatures arrived up here in Boston over the past week, just in time for the peak holiday season, and we’ve even had a dusting of snow. Here’s proof, in case you don’t believe me.

Absolutely brutal temperatures arrived up here in Boston over the past week, just in time for the peak holiday season, and we’ve even had a dusting of snow. Here’s proof, in case you don’t believe me.

Of course, this isn’t stopping teenage boys from walking to high school in just shorts and sweatshirt hoodies, which is yet another reminder that this demographic is wired differently from the rest of the world. Can’t they feel the cold?

The other big news over here is the relaunching of NEJM Journal Watch to NEJM Clinician. You can read more about the changes in NEJM, and in the meantime I’ll continue as an Associate Editor and writing away ID-themed blog posts right here — just like this one. If you’ve subscribed (there’s an email sign-up box to the right), you’ll continue to get notifications via email whenever new stuff appears here.

And if you haven’t subscribed, what are you waiting for?

On to a grab bag of interesting ID Links:

1. An antiviral with activity against dengue virus makes an appearance. In a human challenge study conducted in healthy volunteers, the high dose of the experimental antiviral mosnodenvir lowered DENV-3 RNA load significantly more than placebo, with no reported adverse events. Given the complexity and challenges associated with dengue vaccination, an antiviral strategy would be very welcome.

2. Follow-up blood cultures after treatment of endocarditis are not useful in asymptomatic patients. In a study of 598 episodes of endocarditis, follow-up blood cultures drawn within 14 days after completing antimicrobial therapy detected only two recurrences (≈ 1.5 %) — and both patients had symptoms. Note that 10 other follow-up cultures were positive with a different bug, and work-up ruled out endocarditis. In other words, don’t do this unless clinically warranted.

3. An HIV cure after stem cell transplant — this time with a twist. A 60-year-old man treated for acute myeloid leukemia received an allogeneic stem-cell transplant from a donor heterozygous for CCR5 Δ32 (i.e., only one copy of the mutation), yet achieved sustained, ART-free remission of HIV‑1 for over 6 years. Extensive reservoir testing found no replication-competent virus in blood or intestinal tissues, and HIV-specific antibodies and T-cell responses waned, suggesting the virus may have been eradicated. This is Cure #10*, if you’re keeping score.

(*That last link is to Dr. Samuel Hume’s awesome Substack — he’s a medical resident in England and publishes medical breakthroughs each week! )

4. Online rogue pharmacies, most of them based outside the United States, continue to push ivermectin as a miracle cure. Covid was just the beginning — now we’re deep into using this anti-parasitic agent for advanced cancer and serious neurologic conditions. From the treatment of choice for strongyloides to a leading role in health conspiracy theories and medical grift, ivermectin sure has had an unlikely path.

5. Remove IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors from immunosuppressive therapies that require pre-treatment testing for latent tuberculosis. This welcome consensus statement reminds us that not all biologics* are created equal, and when it comes to TB reactivation risk, most are not in the same league as TNF-inhibitors. As a reminder, IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors (there are lots of them!) are used mostly for treatment of psoriasis, various rheumatologic conditions, and inflammatory bowel disease.

(*What’s the precise definition of a “biologic” anyway?)

6. A single-dose four-drug regimen for malaria was as effective as standard of care. Yes, more good news on the malaria treatment front! The four drugs came in two combination products: sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and artesunate-pyronaridine. Such an approach could greatly improve treatment adherence. This adds to the advance with ganaplacide (a new drug) plus lumefantrine, which I reported on in my annual ID gratitude post. Noting the relatively little attention these studies got in standard ID circles, I checked with my brilliant ID friend, colleague, and parasitology expert Dr. Christina Coyle: “Seems like a big deal! Am I wrong about this?” She confirmed — “Great breakthroughs!” Thanks, Christina.

7. Herpes zoster incidence increases shortly after the first vaccine dose of the vaccine. Data come from an analysis of two large Australian databases, showing an 11-fold increased risk of zoster in the first 3 weeks after the first dose. Most cases were mild, and this was not observed after the second dose; in fact, case incidence declined. Suspect this phenomenon is due to the immune activation triggered by this virus, which can be dramatic — and analogous to the rise in zoster incidence shortly after starting ART in people with HIV.

8. A study of inhaled clofazimine for treatment of pulmonary M. avium complex was halted due to futility. I’ve already branded this drug The Weirdest Antibiotic on the Planet, noting that when given as pills for this indication, “we really don’t know if it works.” It certainly didn’t work in this study, so these results burnish clofazimine’s infamous reputation only further.

9. A single dose of the HPV vaccine worked really well. In this large randomized trial of 20,330 girls aged 12–16, one dose of either a bivalent or nonavalent HPV vaccine was noninferior to two doses in preventing persistent infection with high-risk types HPV-16 or HPV-18 over 5 years. With vaccine effectiveness 97% in all study arms, this strategy could greatly expand utilization of this vaccine in developing countries, where most of the cervical cancer cases now occur.

10. A large series of PCR-confirmed cases of Oropouche virus disease gives a more balanced perspective on disease severity than previously studies. Describing nearly 500 PCR-confirmed Oropouche fever cases in Peru in the first 9 months of 2024, the study reports that patients presented with headache, fever, myalgia, and arthralgias; most cases were mild, but 2% required hospitalization. It’s a reminder that Oropouche virus disease remains a plausible cause of “dengue-like” febrile illness in travelers to Latin America.

11. MMWR reported a recent fatal rabies case in a patient who had received a transplanted kidney from a deceased donor with undiagnosed rabies. The donor apparently had experienced a “skunk scratch” and the virus was of a bat variant — hence bat to skunk to human transmission is suspected. No other cases from this donor have been reported, including three cornea recipients who underwent graft removal and received post-exposure prophylaxis. A reminder that though overwhelmingly safe and beneficial from the individual and societal perspective, organ donation will continue to have a low but non-zero risk of serious infection transmission.

12. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 8–3 to rescind the universal recommendation that newborns receive a first hepatitis B shot at birth. They now advise that only babies whose mothers test positive (or whose maternal status is unknown) get the birth dose, with others left to “individual decision-making.” Since others in our field have extensively weighed in (mostly in protest), I’ll take this space to note that “horizontal” transmission of hepatitis B within households is far more likely with hepatitis B than with HIV and hepatitis C, and that many children diagnosed with hepatitis B historically acquired it from an unknown source. And agree with this headline describing the new ACIP meetings as “beset by incompetence, bias, and procedural chaos.” I like this aside by the author, Dorit Reiss, a law professor who focuses on vaccine policy:

Several observers of ACIP compared the meeting to a clown car, but my husband, Fred, reminded me that clowns are seasoned professionals who work very hard on their shows, and this meeting did not reflect such professionalism.

Oy, one fears for their next steps.

13. Intravenous iron use for treatment of iron deficiency anemia during acute infections was not associated with worse outcomes. A large retrospective cohort analysis of >85,000 adults hospitalized with acute bacterial infections and concurrent iron-deficiency anemia found that those receiving IV iron had significantly lower 14- and 90-day mortality, along with greater long-term hemoglobin gains, compared with matched controls not given IV iron. With the usual caveats about retrospective studies and the difficulty of controlling for baseline differences, and the limitations of conference abstracts, the data nonetheless challenge a long-held assumption (and a widely cited systemic review) suggesting that IV iron is harmful during active infections.

14. It’s not easy being the child of an aging parent with an ID problem. The link is to a story from my life. It includes some nifty drawings by my sister Anne. Hope you find it relatable!

Bundle up, Northeasterners!

(I think that’s a word.)