An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 14th, 2026

Influenza — So Familiar, Still So Mysterious

In what feels like the fastest-peaking influenza season in quite some time, I find myself returning to a familiar answer when asked questions about this miserable virus: “We just don’t know.”

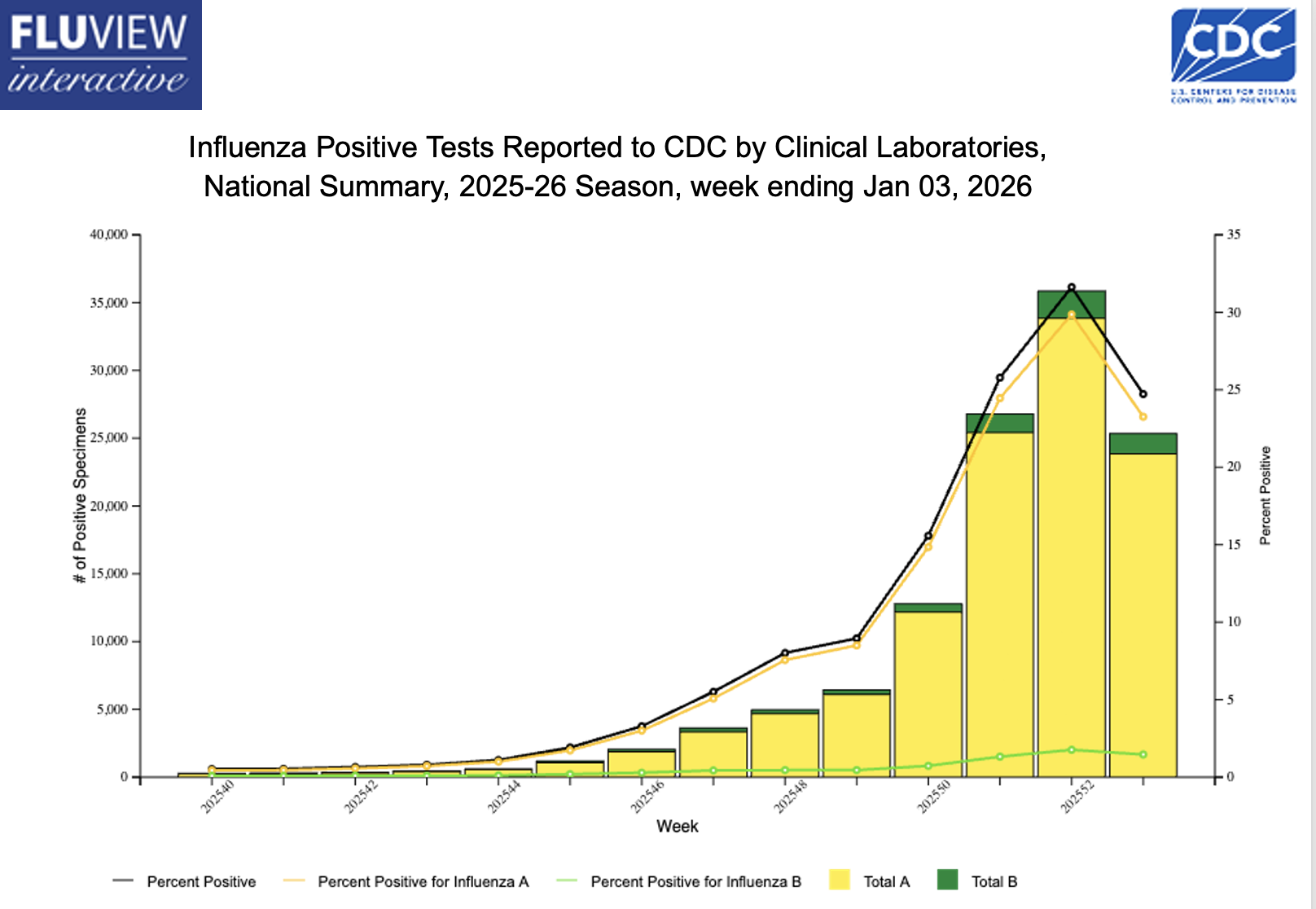

At least I hope it’s peaking — take a look at this encouraging recent trend:

Decline notwithstanding, there’s still tons of influenza activity out there, triggering the usual flurry of questions from patients, friends, colleagues, and the media. I’ll share a bunch of these common questions, along with my best attempt at answering them.

#1: Why do some influenza seasons start quickly, while others don’t get going until later in the winter?

Weather is one common explanation, as temperature and humidity are the most significant meteorological indicators associated with epidemic onset (cold and dry are worse), and their effects vary by influenza subtype — but it seems particularly important with H3N2, this year’s dominant strain. Certainly it’s easy to point at our unseasonably cold December here in the Northeast as the culprit, but it’s not just that.

In fact, the most common explanation this year is the emergence of the dominant H3N2 subclade K (from J). I’ll confess that until recently I didn’t even know influenza had “subclades,” but any viral change that weakens existing immunity can plausibly increase case counts.

Even worse is when there’s a more dramatic shift. Remember 2009? A new influenza A (H1N1) virus, nicknamed “swine flu,” emerged and rapidly spread globally. It caused the first influenza pandemic in over 40 years, including tons of spring and summer cases (that off-season surge was so bizarre), and disproportionately affected children and teens.

H3N2 subclade K isn’t that kind of change, fortunately. To what extent it (vs. the sustained cold weather) explains the intense early flu activity is unclear.

#2: Does the early start to the flu season mean it’s going to be like this the whole winter?

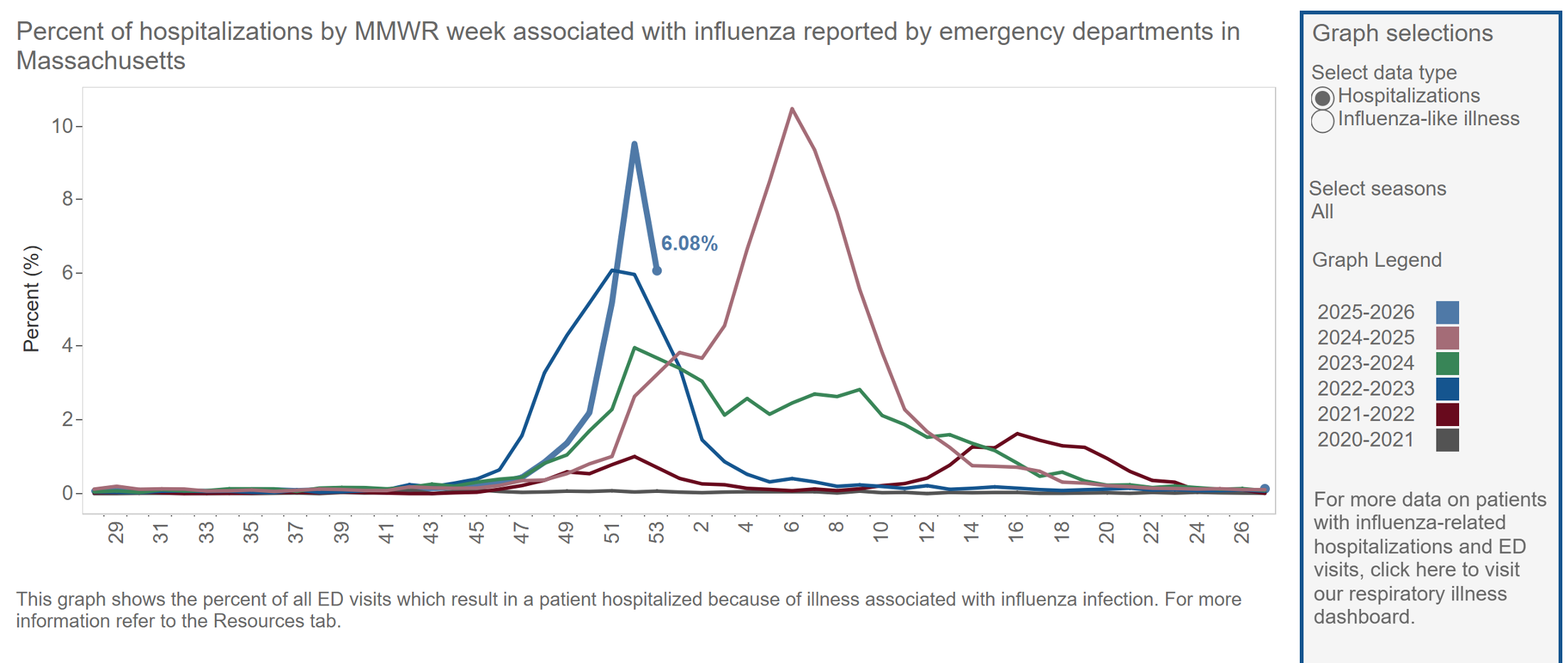

Headlines everywhere the past several weeks blared that we were experiencing the worst flu season in years. Sure, it was a particularly severe start, but the time of onset and duration of the season are separate issues. A season that starts early may end quickly (fingers crossed); another may start and peak later, then smolder for months — the latter is what happened last year, which was a very bad flu season, and which didn’t peak until February.

Some years the long duration of the flu season is attributed to a shift from predominantly influenza A to influenza B; this can also give some unfortunate individuals a second case of flu in the same season. As before, whether this will happen in 2026 is another “we don’t know” reality.

In summary, a season that starts out raging might not ultimately be severe in aggregate. This fact is much less newsworthy, so it doesn’t get the headlines.

#3. Why are we still so bad at predicting dominant circulating strains?

Surveillance is inherently backward-looking. We take a look at the global circulating strains and make a best guess what will hit us, what to put in the vaccine, and what to expect. But viral evolution is unpredictable, so this year’s K subclade isn’t in the vaccine.

In hindsight, the dominant strain can sometimes seem obvious, but in reality, it rarely is.

#4: When there’s crazy flu activity like this, why doesn’t everyone get sick?

Another way of asking this question — why is the household attack rate of influenza only approximately 15-20%? After all, these are people sharing the same room, the same air, the same surfaces as an active case of the flu. If we had a better understanding of host susceptibility, we’d be much better at instituting preventive strategies, like postexposure prophylaxis with oseltamivir or baloxavir.

Take a look at this recently published study for how mysterious transmission is for this winter scourge: Researchers brought naturally infected “donors” (with confirmed active influenza) together with healthy “recipients” in a controlled hotel/quarantine setup, sampled air and surfaces, and yet not a single recipient developed influenza by symptoms, PCR testing, or serology.

A bunch of theories have been posited by one of the researchers, including protective immunity among the volunteers and sparse coughing by the donors, but here’s what I want to know: where can I find a hotel that completely blocks influenza transmission — and can hospitals learn anything from it?

(That was a joke.)

I have a query in to a coauthor what the stipend was for participating as a “recipient” — hope it was generous!

#5: Is the reason for such intense flu activity all the negative messaging about vaccines?

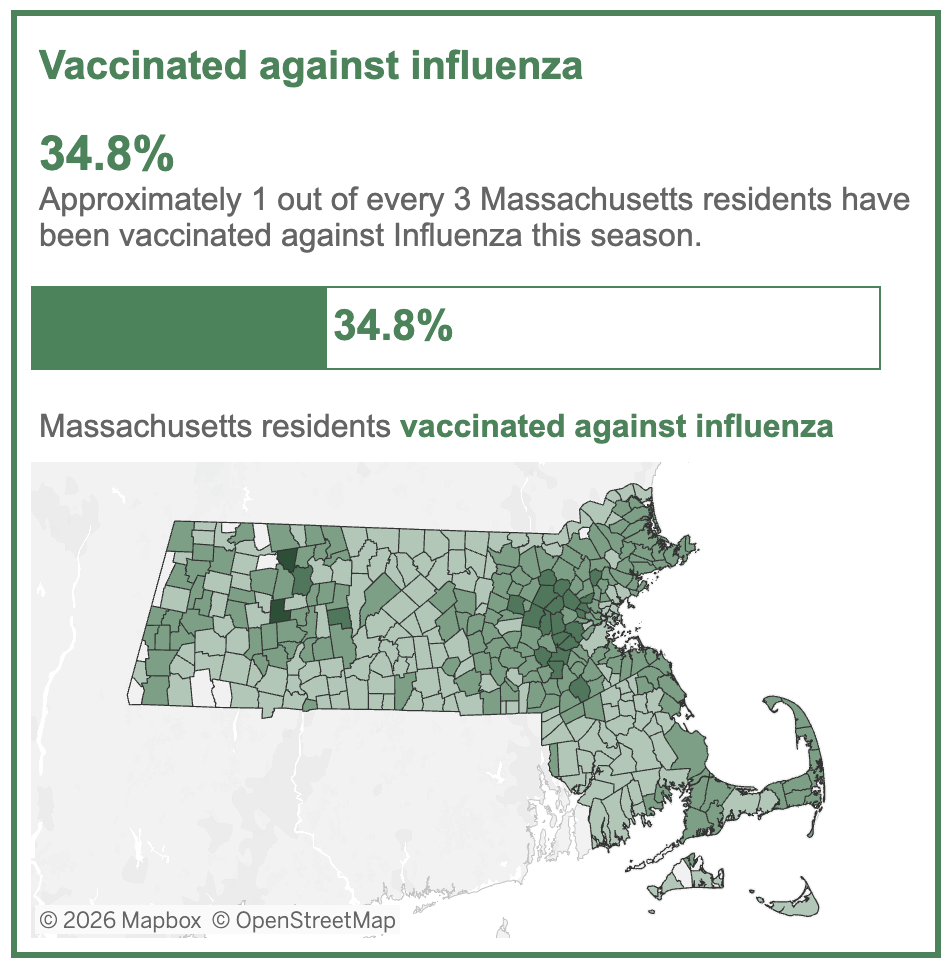

Despite the universal recommendation to give the flu vaccine each year, this year most people have chosen not to do so. Here are data from Massachusetts:

But I’d be skeptical of claims that the rapid start to this year’s flu season was driven by low vaccine uptake. First, it’s no secret that this is not a popular vaccine; even in “good” years for flu vaccine uptake, only half the population chooses to get it. Second, the vaccine has never been great at preventing infection, so it’s not clear to what extent this would play a role for a year where the major circulating strain isn’t even in the vaccine.

Important reminder: studies consistently show an association between getting the flu vaccine and a reduction in severity. hospitalizations, and deaths — and that even seems to be the case in early data from the U.K. involving H3N2 subclade K, especially in children. Get the vaccine, it’s not too late!

Five questions, five variations on “we really don’t know.” Influenza has been with us for millennia and studied intensively for decades, yet it continues to surprise, confound, and humble us. Perhaps that uncertainty is itself the most reliable feature of this most familiar winter virus.

Leave a Reply