An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 15th, 2023

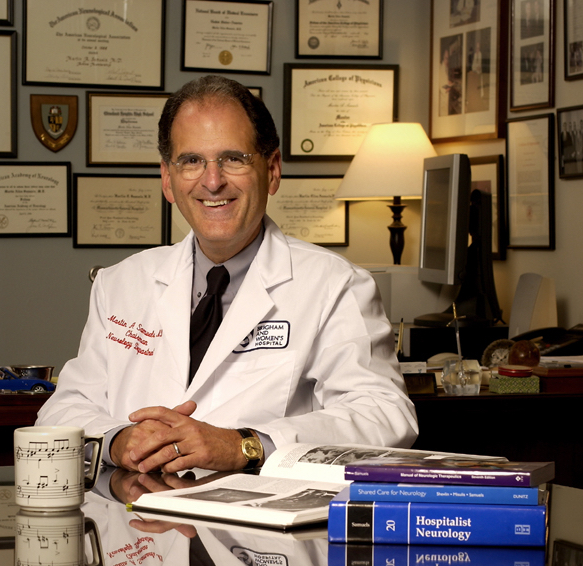

Clinical Teaching at the 99.9th Percentile: Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

No one exemplified this talented group better than Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels, former chief of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (where I work), and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He was quite simply the best clinical teacher I’ve ever encountered.

Marty died last week, and our world is sadly now a less interesting and less fun place. What made him so special? Here are a few thoughts:

He had endless enthusiasm for clinical neurology. You could just see his eyes light up when a resident presented him a case. The combination of clinical problem solving together with a group of trainees eager to learn visibly energized him.

And the enthusiasm didn’t end with neurology. He embraced all of medicine, including its history, which he loved to connect to neurology — cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, ID. Watch him discuss a case of an older man with mental status changes during a “virtual” Neurology Morning Report, done on Zoom during the pandemic. He deftly describes his clinical reasoning, interweaving Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, pathophysiology, and his experience working with the great British hepatologist Dame Sheila Sherlock.

Note also the natty cartoon Dalmatians bow tie, both very New England-academic and very mischievous at the same time. So Marty.

His lecture topics often had simple titles: Dizziness. Headache. Dementia. Weakness. But they were hardly simple. No one who has heard his talk on dizziness forgets the first thing to do when a patient says they are dizzy. Namely, you pause, and repeat back — Dizzy? — and let them explain what they really mean!

He always knew his audience. One of the most difficult skills for clinician-teachers is explaining complex topics to people outside their field. (For you ID/HIV docs out there, just try to summarize the available antiretroviral agents. Ouch.) Experts routinely forget how to communicate with non-specialists — they are so immersed in their work that they assume everyone understands their arcane language.

Not Marty. He intuitively pitched his talks at the perfect level for the learners. You came away knowing that he was a true expert, but you were never baffled (or bored) by minutiae or jargon.

I have given a talk to the medical residents on, well, how to give a good talk. (I hope it’s a good talk!) Here’s one of the slides, with the Key Message repeated 4 times for emphasis — it’s that important:

Marty embraced this principle better than anyone.

He never let technology take center stage. Marty’s slides were often bare bones, just a few lines of text. His lectures were about what he was saying, not what he was showing. I heard him speak on dementia at a large medical education conference when the slide system failed; there were hundreds of clinicians in the cavernous conference hall. No matter — he held them spellbound with just his extemporaneous comments, presenting a few clinical cases and how he’d approach them. Everyone left with a clinical pearl they could apply to their practice.

If anything, Marty’s talks were better without slides. Anyone eager for a refresher on how to do the neurologic examination can find a 7-part (!) series on youtube, just him and a sample patient — no slides. Here’s a brief clip.

He wasn’t shy about expressing his opinion. Marty was the longtime editor of NEJM Journal Watch Neurology, so we attended several editors’ meetings together. One memorable time, the assembled (myself included) were trading ideas about how to keep up with the ever-growing volume of research, citing newer (at that time) techniques such as listservs, signing up for electronic tables of contents (“eTOCs”), and message boards.

Marty didn’t participate in the discussion — until finally, he said, “Isn’t it more important that we get it right, rather than get it fast? Because I confess this entire conversation fills me with a profound sense of ennui.” That ended the discussion!

He deeply distrusted “systems” that attempted to interfere with clinical care in the name of efficiency for efficiency’s sake or, even worse, just to save money. He found it particularly ironic that many of the very people espousing such systems would, when confronted with an illness in themselves or their family, immediately try to circumvent the system they had created.

He wasn’t shy about giving a name to this practice, either — specifically, hypocrisy. I encourage you to read the linked post, it’s a classic.

He wasn’t afraid to share the fact that he made mistakes. We all make mistakes — we’re human, after all — and Marty believed that these mistakes make us better clinicians when we think through why we made them, and what we can learn. One of his very best talks even had the title, “What My Mistakes Taught Me”, and he commissioned a bunch of us to come up with similar talks. What a challenging exercise!

He likened these mistakes to the genetic errors that get weeded out through evolution. We don’t try to make a mistake — but they happen. We acknowledge it. Analyze why it happened. We then learn from the error, with the goal of not making that mistake again.

Evolution at work.

He was funny. So very funny. A colleague recently told me that Marty did stand-up comedy after graduating from college, and I’m not surprised — his timing was perfect. I remember he gave medical grand rounds several years ago, and began it with a particularly good joke, but one that would easily qualify as “blue” humor. Let’s just say that my editors here at NEJM Journal Watch would never let me repeat it in this post.

After he got a big laugh (and he always got a big laugh), he looked at us and said, “That joke has nothing to do with my lecture. I just wanted to see if I could get away with saying it in front of the Dean of Harvard Medical School, who I knew would be attending today.”

Even bigger laugh.

Wrapping up, I can do no better at showing what a captivating speaker he was than to share this talk he gave just over a decade ago at an ethics forum run by the Massachusetts Medical Society — our publisher. It’s an excellent use of 25 minutes of your time, but if you’re busy, start at 16’43” when he presents a case he saw for discussion.

Rest in peace, Marty. We’re really going to miss you.

Really lovely tribute, Paul. Thank you.

That last video is brilliant.

Thank you, Dr. Sax, for this lovely tribute to Marty, the consummate clinician-teacher without parallel in my experience. I was on Neuropathology and Neurology staff at BWH for six years in the 90’s and it was just wonderful interacting with him on a regular basis. There is only one anecdote I can add and what I see in Marty that is so remarkable and this his almost child-like enthusiasm for Neurology that never flagged. During the monthly brain cutting sessions that I conducted, he would always attend when he is on service and while “cutting” the brain, I would toss out questions along the way. Invariably, Marty would jump in to answer the questions, like punching in quickly on “Jeopardy”, until I reminded him that the questions were addressed to the students and residents who are in attendance, not him.

Thank you again. Your tribute brought back a flood of great memories of him.

As you describe, Marty, was a true triple threat and more. He pushed us to do what was right for patients. I made sure to attend his lecture at any conference I went to. He was an outstanding model we should aspire to be as close to as we can. I use his teaching on “ Dizzy” every month on teaching rounds

A fantastic tribute – brings back so many good memories of this incomparable clinician educator. Marty held us spellbound whenever he taught us, in whatever context. Thanks!

Adding my thanks, Paul, for this tribute. I strongly considered neurology as a specialty based on my experience on my clerkship with Marty. Yes – I hear his voice every time I evaluate a patient with dizziness and it brings a smile to my face. As an educator I know how hard it is to really be an expert educator but Marty did so effortlessly, and, as you said, with humor. I’m looking forward to watching the clips you hyperlinked to educate me further and to remember a great man.

Thanks for the comment, Wendy. By coincidence, I just got an email from another ID doctor that they considered neurology based on working with Marty as a medical student!

Watch the MMS Ethics Forum video. It’s mesmerizing.

Paul

Thank you for a wonderful tribute. Dr Samuels traveled to Pittsburgh often to speak at our family medicine refresher course and at grand rounds at our family medicine residency program. I also heard him present at the American Academy of Family Physicians national conference. He embraced and validated the work of primary care physicians in every venue in which he taught us. His approach to the chief complaint of dizziness is a classic for the ages. Rest in peace, Dr Samuels. We will miss you.

I am stunned. Such a loss. I can still see him standing on the stage posing as a neuron, waiting for something to do.

Your comments on Marty skills are superlative. I have so many thoughts about him that this message space is simply inadequate. I would like to add one which is the empathy he brought to his foundation of scientific knowledge. Every patient meant something to him. You could see it in his face. In the end, he influenced the care given to millions of people. Imagine lecturing to hundreds of thousands of physicians during your lifetime. Imagine the number of patients who benefited from that transferred wisdom.

Thank you for this tribute to Dr Samuels! As a novice general internist in the early 90’s I attended his lecture on headaches at a CME event in Boston – after that I was “hooked”. Attending many more of his conferences, often specifically dedicated to us (primary care physicians)!

His demonstration of festinating gait is impregnated in my clinical brain and I use it when teaching students.

RIP Dr. Samuels. Your legacy will live long.

Dr. Sax, thanks so much. I trained at BCH and still work at BMC. I was fortunate to hear Marty speak several times. He was an amazing person, and very incisive in his thinking. But the best part was his humor while speaking. Thanks C Bliss Jr MD

“He deeply distrusted “systems” that attempted to interfere with clinical care in the name of efficiency for efficiency’s sake or, even worse, just to save money. He found it particularly ironic that many of the very people espousing such systems would, when confronted with an illness in themselves or their family, immediately try to circumvent the system they had created.

He wasn’t shy about giving a name to this practice, either — specifically, hypocrisy.”

So true. Wonder how many healthcare administrators read his post.

Thanks Paul. So well expressed and all so true. Making Neurology Rounds with Marty in the back buildings of the Brockton VA was an indelible experience. Then again, so was any time spent with him or listening to him at BWH.

A beautiful tribute to Dr. Samuels. I think you share many of those praiseworthy qualities, as well.

And I hope you keep writing this blog!

I completely agree with Dr. Sax’s Observatios. I just want to point out I went through the last video or, following his suggestion, from 16’43’’ on, and I found an extraordinary man giving an extraordinary “simple” talk. Simple things made by extraordinary people are just enjoyable. Thank you Dr. Sax… and thank you Dr. Samuels.

Thank you Paul

All of us carry many memories of Marty. Most striking for me is our first encounter. I was an intern at the MGH, Marty was a neurology fellow. I was hopelessly, overwhelmed. Marty, understanding this, kindly walk me through what I needed to know. His kindness overwhelmed me.

Through the years, Marty taught in every Harvard CME course I directed. I’ve heard virtually every lecture multiple times, but each is fresh. When I look at evaluations, Marty continues to lead to pack, as recently as earlier this year. The comments from course participants express all of the sentiments noted. Marty was the only speaker to ever get a 4.5 on a 4 point scale.

Marty taught thousands of doctors and improved their care. This is turn, improved the lives of millions of patients. We can only aspire to achieve what Marty achieved.

I was fortunate to have been a classmate of Marty’s at U of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Class of 1971. His enthusiasm for medicine and neurology never flagged, and it was contagious. At the end of our four years, we put on a senior show “Hirsutism” (“Hair” was popular on Broadway at the time) and Marty was the star of the show (rehearsals were hard because when he was in a skit, we could not stop laughing). He also was one of its main authors.

Over the years, he was always responsive to me when I had a neuro patient that was puzzling. He helped by always being right. Dr. Sax is spot on in his description of this brilliant and nuanced physician.

With all the accolades and thanks from so many over the years, Marty always remained humble and down-to-Earth. His passing is a huge loss.

Barry Mennen

I did my Neurology clerkship with Marty and had the fortunate and indelible experience of being a Neurology trainee with Marty as the chair. No matter how hard the service was or the grueling night of call we could always look forward to Morning Report to discuss our clinical cases and be dazzled by the sheer medical and neurological knowledge that Marty and Allan could banter back and forth between the two of them. It was like listening live to a studio show every morning filled with humor, good cheer, and endless stories on the truly human art of medicine. Thank you for sharing these words and memories of Marty. He was a consummate educator and clinician who has touched so many lives through his superb dedication to the field and inspiration to generations of trainees and practicing physicians alike.

Every med student and resident should be so lucky to have a “Dr. Samuels experience.” In my career, I had more than one and 50 years after graduation I remember them as if it were last week.

I was a nervous student during a medical school rotation, and Marty was my attending. He made me feel “at home” at a strange hospital (the West Roxbury VA) immediately, and always remembered me years later when I’d run into him at the Brigham, even though I didn’t go into neurology, and in hindsight wasn’t a particularly strong student on that neurology elective.

Didn’t matter — he loved teaching so much that he cherished all his learners.

I was in Marty’s medical school class. We all remember his lecture to the teaching faculty at graduation that brought “boos” and some people getting up and leaving. This lecture didn’t have much humor in it!

Anyway, I became a Neurotologist and one of the few “Dizzy Docs” in the country. I never had the pleasure of hearing his lecture on “dizziness” but, would love to hear it if it’s available. Thanks to all for their memories.

At large primary care CME meetings, I always made a beeline for his lectures. I would be caught up immediately in the topic (whatever it might be) by his potent combination of enthusiasm, energy, humor, insight, charm, wisdom, humility, and above all a wealth of practical and useful information. I always left one of his lectures feeling recharged. It reminded me again and again of why we went into medicine in the first place… and I wondered how he kept up the momentum through his long and busy career. He transcended the mundane and repetitive bureaucracy and stress that overwhelms all of us daily. He was the model of a medical mentor that is very rare in the field today and his ability to inform with tacit knowledge has become a lost art. He will be sorely missed.

What a loss! I just saw this in my backlog of emails. I first came across Dr. Samuels at an SHM conference years ago and heard his talk on missed diagnoses and I was hooked. I looked for him at any conference thereafter and was never disappointed. Thanks for your tribute and additional links.

Marty and I kibitzed back and forth between the II & IVth Harvard Medical Service and Vth Boston University Medical Service at Boston City Hospital in 1971 over where an interesting patient might be admitted. Later we resolved such hot discussions with the ‘Meningitis Notebook’ at the Massachusetts General Hospital emergency ward. Marty was a wonderful foil in a debate format and over the decades we parried back and forth regarding such issues as the ‘real history of vitamin B12 at Harvard’ ‘what was the back story on the history of the Neurology Service at Boston City Hospital {standing in equal awe against Bud Rowland’s redux of that era)’, ‘the race between Boston City Hospital and the Brigham over the origin of fasciculations in motor neuron disease in the 1940s’, ‘and ‘my HMS Boylston Medical Society essay on the pathophysiology of sudden death caused by voodoo and hoodoo’. It seems like yesterday when we last joined our wives for a drink at the AAN in Vancouver BC to dwell on past and future memories. Marty emailed me a year ago about a point from my first paper with Ray Adams on cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers that differentiated alcoholic and non-alcoholic seizures that he reintroduced during rounds at the Brigham. His cerebrum was operating non-stop collating facts from fiction and sharing his insights with all. I have been honored to call him a friend.