An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 29th, 2025

How the Z-Pak Took Over Outpatient Medicine

Chances are, across this great land of ours, right at this very moment, someone is coughing, or sneezing, or struggling with a sore throat, or some combination of the above, and taking the antibiotic azithromycin. Or they might be just fevering, with no discernible cause, and still they’re taking azithromycin.

They might have obtained it from an urgent care clinician, an online telehealth service, a supply they had stashed away “just in case,” or any number of sources that most likely didn’t assess whether the benefit of taking the antibiotic outweighed the risk.

Here’s the thing — there’s a very high likelihood it’s doing them no good at all, and there are a bunch of reasons why it might actually be harmful. As an example, more than a decade ago, I wrote about data linking azithromycin to increased cardiovascular events.

Before we get to this and other problems with azithromycin (Part 2 — it’s coming!), let’s take a look back at the history of this extremely popular antibiotic and how it achieved its pre-eminent position in outpatient medicine.

Erythromycin: An Antibiotic That Packed a Punch (to the Gut)

Back during the Ronald Reagan years, the macrolide antibiotic erythromycin was the leading alternative to penicillin. Widely used in people with penicillin allergies — real or otherwise — erythromycin nonetheless had several disadvantages, the most important of which was an incredibly high rate of gastrointestinal side effects.

Nausea. Abdominal cramping. Diarrhea. Bleh.

Typical doses were 250 mg four times a day, or 333 mg three times daily, often prescribed for a week or even longer. The thrice-daily 333 mg dose was more convenient, and supposedly better tolerated, but frankly sparing that 1 mg/day didn’t do much to reduce its side effects.

True story — my first attending physician in a medical school hospital rotation was a gastroenterologist. He’d come down with the sniffles, and he told us he started himself on erythromycin “just in case” (second time I’m using that phrase).

A couple of days later, he didn’t look so great — all pale and sweaty. Trying to be compassionate, I asked how he was feeling. His response: “The cold is better but the nausea from the erythromycin is a killer.”

Oh Physician, heal thyself! Erythromycin doesn’t treat colds!

(I did not tell him that. I was a third-year medical student.)

The New Kids on the Block: Clarithromycin and Azithromycin

Then, in 1991, with much fanfare, two new macrolides appeared on the scene — clarithromycin and azithromycin. Both promised to improve on erythromycin by treating a broader range of pathogens and, most importantly, having fewer side effects.

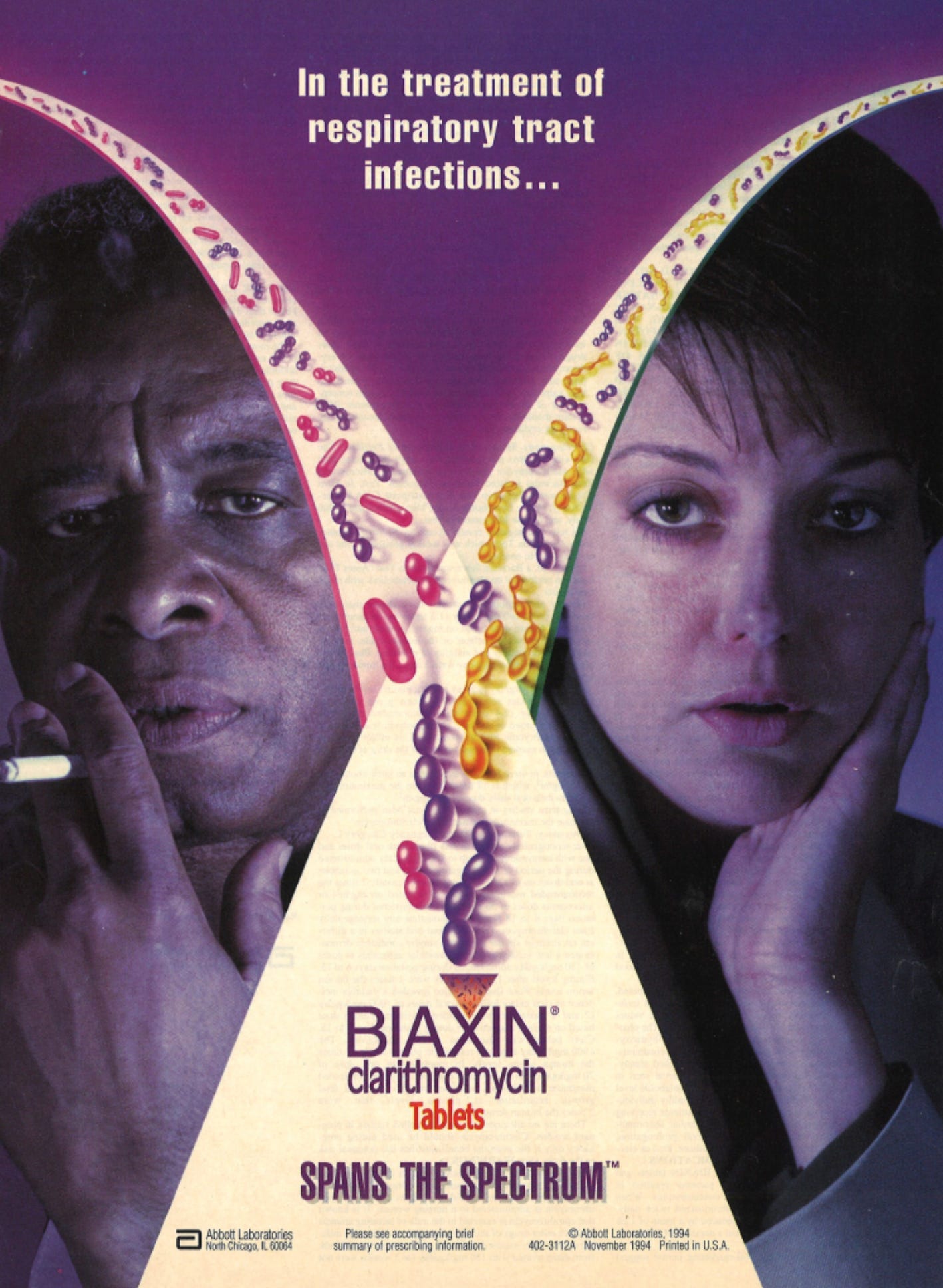

Hooray for both! Advertisements for Biaxin (clarithromycin) and Zithromax (azithromycin) bombarded doctors in medical journals. Paging through the latest issue of The New England Journal of Medicine or The Lancet, we might come across something like this:

Source: Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

Drug advertising back then was a huge source of revenue for medical journals — remember, this was before the internet. The makers of Biaxin and Zithromax were not shy about their new and improved versions of erythromycin, which really were objectively better in many ways.

We don’t hear much about clarithromycin anymore, and for good reason. Glossy ads notwithstanding, clarithromycin never quite delivered on its promise. It also caused GI side effects (though fewer than erythromycin), had major drug interactions, prolonged the QT interval, in some studies increased mortality — and could make food and drink taste absolutely bizarre.

The medical term for taste disturbance is dysgeusia, by the way — pronounced dis-GYOO-zee-uh, which kind of sounds like what it means. You’ll win big points among your friends if you casually drop this word into everyday conversation.

Another true story: A colleague of mine from a prestigious academic medical center in Baltimore boarded a flight to Europe and was upgraded to first class. Handed the complimentary glass of champagne, he tasted it and nearly spat it out. He insisted to the flight attendant that it was flawed and asked for a glass from a different bottle — which, to his disappointment, tasted the same.

Only later did he realize that the clarithromycin he was taking for sinusitis made everything taste like he was drinking from a rusty metal pipe.

So the real champ in the Battle of the New Macrolides was azithromycin, which had a few tricks up its sleeve that made it irresistible to clinicians and patients alike:

- It had fewer side effects than clarithromycin. None of that dysgeusia weirdness. (It’s fun to write, and to say, dysgeusia. I’ll stop doing so now, promise.)

- It had fewer drug interactions.

- It didn’t affect cardiac conduction quite as much, an important safety feature.

- Most importantly, it stuck around in the body for a very long time. The half-life of azithromycin is a stellar 68 hours (nearly 3 days)!

Pharmacologists oohed and aahed over this aspect of azithromycin, which was made even more impressive by its high concentrations within cells and tissues — where it lasted even longer than in the blood.

Enter the Z-Pak. Read on!

Z-Pak Reigns Supreme: The Rise of Azithromycin

What truly transformed azithromycin from a useful antibiotic into a cultural phenomenon was the way its pharmacology was leveraged into the first truly “short-course”

antibiotic.

Instead of the traditional antibiotic regimen (three or four pills a day for 7 to 10 days, ideally taken with food but not dairy, dispensed in an orange plastic bottle with a white cap), azithromycin came as six pre-packaged pills.

Generated by AI but trust me — it looked like this!

Here were the directions:

- Day 1: Two tablets (500 mg total) once

- Days 2 through 5: One tablet (250 mg) daily

Just six pills. Just 5 days. The Z-Pak is born!

The now-iconic Z-Pak took a concept from a pharmacokinetics lecture and turned it into something instantly graspable for clinicians and patients alike. A tidy blister pack. Clear instructions. A sense of completion. You finished it, decisively, in less than a week. For busy clinicians and busy patients, it felt like modern medicine at its best.

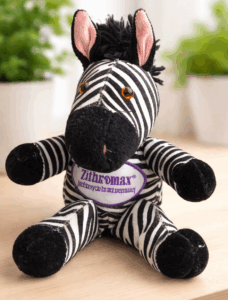

Marketing, of course, played a major role, most notably when the approval was broadened to include children, who got away with taking just 3 days. This is the United States of Advertising, after all! We’d expect nothing less.

At pediatric hospitals and in outpatient clinics, replicas of Max the Zebra — the drug’s mascot, “ZithroMAX”, get it? — dangled from stethoscopes. Medical journals arrived wrapped in zebra-striped covers. Branded stuffed animals appeared in exam rooms to comfort anxious children. In one particularly cringey moment, a real zebra was donated to the San Francisco Zoo by the drug’s manufacturer, and ceremonially named … Max. What else?

Patients (and their parents) loved the Z-Pak. Compared with antibiotics that came with frequent dosing and frequent side effects and difficult-to-open plastic bottles, the Z-Pak felt so efficient.

Add the rise of patient-satisfaction metrics to go along with the advertising, and a health care system increasingly optimized for speed and convenience, and azithromycin found itself perfectly positioned. It became the antibiotic people expected (and asked for by name — I want a Z-Pak!), and clinicians reached for reflexively.

That dynamic has only intensified in the modern era, particularly with the expansion of telehealth. Final “true story” of this post: During the pandemic, a physician colleague of mine shifted to doing exclusively telehealth for a large national company — a model that suited him well, allowing him to travel freely and spend time with grandchildren scattered across the country, mostly in warmer climates.

When I asked him which antibiotic he prescribed most often in these virtual encounters, his answer was instantaneous: azithromycin. In settings where the examination is limited, diagnostic testing is unavailable, and the encounter is brief, the Z-Pak becomes the path of least resistance.

That convenience helps explain how azithromycin came to dominate outpatient prescribing. Whether that dominance has come at a cost will be the subject of Part 2, despite the fact that I have already written far more words about the Z-Pak than I ever imagined possible.

(Source of vintage zebra image at top: publicdomainimages.net.)

FYI for those of us who read on our phones the new format is impossible.

Hi Jan, sorry about that, it’s frustrating for all of us. I know they are working on fixing it!

– Paul

I have frequently joked that urgent care center waiting rooms should take the the old cigarette dispensing machines and fill them with Z-paks. Everybody gets one when they leave anyway. Would save time!

A highly relevant cartoon!

– Paul

Dear Dr. Sax,

I’ve been folowing your articles for decades. I love them: humor and eduaction.

Question: In the setting you’ve described, examination is limited (or none), diagnostic testing is unavailable, and the encounter is brief (or none, or by video, or by a phone call), which antimicrobial would you choose for what seems like a “common cold”, but suspiciously complicated by a bacterial infection?

Thank you.

Thanks for reading! Doxycycline is a good antibiotic for outpatient bronchitis. Trim sulfa, amox clav, and cefpodoxime would be other reasonable choices.

-Paul

I was trained to treat Bronchitis with an inhaler not antibiotics. Is this the newest thing

Bronchitis responds to neither azithromycin nor an inhaler. It is a viral infection without bronchospasm. It is nothing more than a chest cold. The exception would be the patient with COPD.

Bronchitis is VIRAL 95%+ of the time. Doxy, SMX-TMP, amox, etc are NOT indicated. Bronchitis does not equal bacterial tracheitis, which is not common. Loved the article so far, but this response was underwhelming. Thank you for this article, you addressed one of my greatest irritants. Azithromycin is not a first-line drug for anything.

And patients ask for it by name! And insist it is the only antibiotic that ever works on anything they might have. Any respiratory illness (upper or lower), and they want their Z-Pak. And they get quite annoyed if denied their favorite antibiotic. I teach my students that Z-Pak is one of the best examples of the wonders of pharmaceutical marketing.

Hi Dr Sax. Enjoy your comments. However I think you went a bridge to far, at least with the referenced study (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38666.653600.55), then stating, “Clarithromycin… in some studies increased mortality…”.

In short, this study randomized ~4500 patients with significant history of CVD to 2 weeks of Clarithromycin 500mg daily or placebo, hypothesizing that the active treatment (of nothing, btw) would have deleterious effects. The outcome was that neither the pre-specified primary nor secondary composite outcomes were different in the 2 groups. End of story, anything else dredged from the data, including any difference on one of the composite outcome components, is only hypothesis generating, at best.

Unfortunately, our friends in Pharma have been pulling this statistical sleight of hand for many decades, in an attempt to misrepresent one of their or a competitors drugs. Of this I know as certain after spending 26 years working in that arena.

I’ll chalk this slip of the statistical tongue to, as Scrooge laments seeing the ghost of Marley, “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato.” All likely would have tasted a bit off-putting if Scrooge was taking Clarithromycin. Happy holidays!

Thanks for this great comment and analysis, David. The study of concern was aiming to reduce the risk of coronary artery disease via treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae, a popular cofactor theory at the time (now abandoned) — yet they found that the treatment was harmful. And just to continue in support of a real safety concern, there also was a signal for increased mortality in a study of people with HIV who received higher doses of clarithromycin.

https://doi.org/10.1086/520141

Plus, as I noted at the very top, there is even a warning about azithromycin and CV events.

-Paul

Many patients in my primary care HIV practice insist that they feel better after AZI. I first encountered this experience when my non neurotic radiologist friend and mother or 3 noted that her kids symptoms waned impressively with macrolide treatment–back in the late 1990s when we worked together. I always believed this was coincidence.

But then the notion of AZI anti inflammatory effect was embraced–initially in the Asian Diffuse Panbronchiolitis experience, then for CF and now for non CF chronic bronchiectasis, where AZI is touted to reduce exacerbations as outlined in this meta-analysis. by Li et al.

Li K, Liu L, Ou Y. The efficacy of azithromycin to prevent exacerbation of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022 Oct 11;17(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s13019-022-01882-y. PMID: 36221151; PMCID: PMC9555173.

So, I am not sure if all your disdain for the the practice is warranted or “evidence based”.

In my recollection, some practices justified by RCTs were actually embraced by patients first–such as stopping PJP prophylaxis after ART and using combination ART–albeit DDI, AZT before combo ART was the standard. Let us not forget, that evolution in nature occurs by trial and error, not by RCT.

Appreciate your perspective! Am sure that some people feel better getting something rather than nothing.

In my defense, here’s a typical double-blind clinical trial comparing azithromycin to vitamin C in acute bronchitis. The curves of time to improvement overlap with remarkable precision!

-Paul

Maybe vitamin C is also effective–another putative beneficial tonic, along with chicken soup, tea and Tylenol.

Academics would demand a true placebo controlled RCT–stratified by chickensoup use, ginger use, etc.

Expanding on my last comment–clearly too much time on my hands–The hallowed RCTs contribute to the problem of overprescribing. When a drug has a slim statistical benefit– like paxlovid or oseltamivir, for example, the vast majority of patients who take it probably derive little benefit. Yet, their use is sanctified by RCTs. If we don’t know the etiology of symptoms, we can’t precisely deploy treatments.

I was surprised to not see mentioned on of the largest problems of the popularity of using “Z-paks” for most anything, even when not indicated. Beyond fueling the patient expectation of “I just need an antibiotic”, such wide usage is definitely diminishing it’s efficacy when it is indicated.

“Part 2” is coming!

-Paul

There was a marketing problem with the Z-pak . What to do with the patients who completed their 5 days of antibiotic and were still symptomatic? Give them another Z-pak? Switch to something else? There was an advertising campaign specifically to address this problem, encouraging prescribers to “stay the course,” and tell the patients their symptoms might outlast the Z-pak, and that that was expected. The print advertisements featured people surfing in purple wet suits. The theoretic justification was that 3-day half-life. But it was pretty clear what was really going on: if your treatment doesn’t have an effect, persuade the patient that natural recovery is a treatment effect.

A month ago, I consulted on an 18 yo son of our hospital nurse who had the cough, sore throat, fever and was given amoxicillin with no help. 8 days later he came to ER with ataxic gait and all tests negative except Mycoplasma. Within 24 hours he lost strength in both legs then both arms and was given IVIG. But CSF with 40 wbc with elevated protein. He then developed loss sensation to the nipple line. Was started on high dose IV solumedrol and transferred to Stanford where he was continued on high dose solumedrol and progressively worsened and ended on ventilator support. MRI showed entire spinal cord abnormality all the way to the conus and also with Bilateral optic neuritis. He was treated with plasmapharesis and toclizumab infusions with no benefit. He finally came off ventilator but has feeding tube and still totally paralyzed. They ran millions of tests at Stanford and the only positive result was the mycoplasma. I kept wondering whether a Z pack for the mycoplasma might have prevented all this. Witnessing how this young man’s entire nervous system was dissimated, I will certainly take my Z pack when that viral syndrome keeps lingering.

No doubt azithromycin still is useful in some cases! Stay tuned for Part 2.

-Paul

As an emergency physician for 25 years who has recently transitioned to telemedicine, I dread the daily fights with patients who insist on a Z-Pak for every respiratory infection. Two comments:

1. Although telemedicine and urgent care do likely prescribe a lot of Z-Pak, over my 25 years of emergency medicine it seems to me most patients get them from their primary care providers.

2. The power of the placebo effect is very strong and just taking some prescription seems to make most patients feel better. (“ The over-the-counter meds aren’t working for me Doc, I need a prescription!“) Before the Z-Pak I think penicillin and amoxicillin were also used fairly frequently for a lot of likely viral respiratory infections. Perhaps we need to create and market a P-Pak- placebo pills to harness the placebo effect in making patients feel better faster??? There used to be Obecalp, placebo spelled backwards….

I remember another distinct benefit to its success: For physicians only had to write “Zpak” on their Rx pad, sign and date it, and check 1 for quant and 0 for refill and it was filled. Very efficient. Although oral contraceptives came with explicit instructions, the prescribing physician still had to squeeze in more info on that tiny pad. The reps knew about this time saving shortcut available and readily marketed it to busy practices.

Vit C curve overlapping Azithromycin curve = Linus Pauling! LOL!!

going back to the earlier history you cover, I have always thought (without a ton of data for proof..) that erythromycin prescription-writing ratcheted way up after 1976 and the initial Legionnaires’ outbreak in Philadelphia, when erythro treatment was empirically the most effective. It then seemed to become the standard Rx for suspicion of any community-acquired pneumonia (along with influenza and cold symptoms..) since the coverage for atypical bacteria, Legionella, etc etc was much greater than that of the penicillins, which seems to lead to your slippery slope toward the Z-pack. Anyone know of any data from late 70s-early 80s supporting this?

I would argue that the Z-Pak has been one of the most persistent disruptors in clinical practice during my lifetime. It hit the market when I was a kid, and since starting practice 22 years ago, it has been a source of ongoing debate. To be fair, azithromycin still has a role in very specific scenarios—but that hardly offsets the countless hours spent explaining why it isn’t the universal cure patients expect.

For eight years, I worked in an acute care setting where clinicians were aligned: a Z-Pak alone is not first-line therapy for any respiratory condition. That consensus was clear and evidence-based. Now, in my current role, I’m seeing Z-Paks not only prescribed routinely but even promoted to new clinicians as if nothing has changed since 1989. It’s a stark reminder that old habits die hard—and that this one medication may continue to haunt us for years to come.

Adam,

Very well said! Appreciate the comment.

-Paul

There aren’t many columns that bring back memories from they day the Pfizer rep sampled Z-paks to my family medicine residency AND a phone call in clinic yesterday. “I’m flying to Argentina in 2 days. I’ve had sinus congestion for 7 days. I’ve got a Z-pak that’s not expired.Can I take it?” FWIW, when I was that resident, even my highly respected and published ID mentor said off the cuff that when he got “sinus” he jus took a Z-pak from the sample room. In medicine the questions never change, but the answers do.

This column was a wonderful trip down memory lane. It also made me recall the times when patients expressed their anger and told me that as a young family physician, I was incompentent when I refused to prescribe Z-packs for their viral URIs and bronchitis.

Thanks, Richard! Part 2 gets at the problems with all that azithromycin use.

https://blogs.nejm.org/hiv-id-observations/index.php/how-the-z-pak-took-over-outpatient-medicine-part-2-the-reckoning/2026/01/06/

-Paul

I had three young children when a colleague pulled me out of my clinic before the Drug Rep gave away all her stuffed zebras.

She offered one but I said, “You can give me 3 or zero, but not one!” I usually eschew branded merchandise but these Zebras appeared in many Noah’s Ark and letter Z preschool events.

Decades later my grandsons play with them — along with the Rhinocort Rhinoceroses!